Modern regulatory and certification audits are becoming continuous verification processes, not episodic events. For many organizations, this shift creates a significant operational challenge: audit evidence is often collected late, scattered across disparate systems, and assembled under immense pressure. This reactive approach is inefficient, risky, and fails to meet the standards of today’s auditors and regulators. The core problem is treating evidence collection as a documentation task rather than an engineering and governance discipline. This guide explains what audit evidence is, why it is a critical component of modern compliance, and how to build a systematic, verifiable approach to its management. Readers will learn the properties of strong evidence, common management failures, and the principles for designing a system that ensures continuous audit readiness.

What Is Audit Evidence

Audit evidence is the verifiable information an auditor uses to determine whether an organization's controls, processes, and systems conform to a given standard, regulation, or policy. It is the objective proof required to support an audit opinion. In practice, audit evidence moves an organization's claims from assertion to demonstration, answering the auditor's fundamental question: "How can you prove this control is operating effectively?"

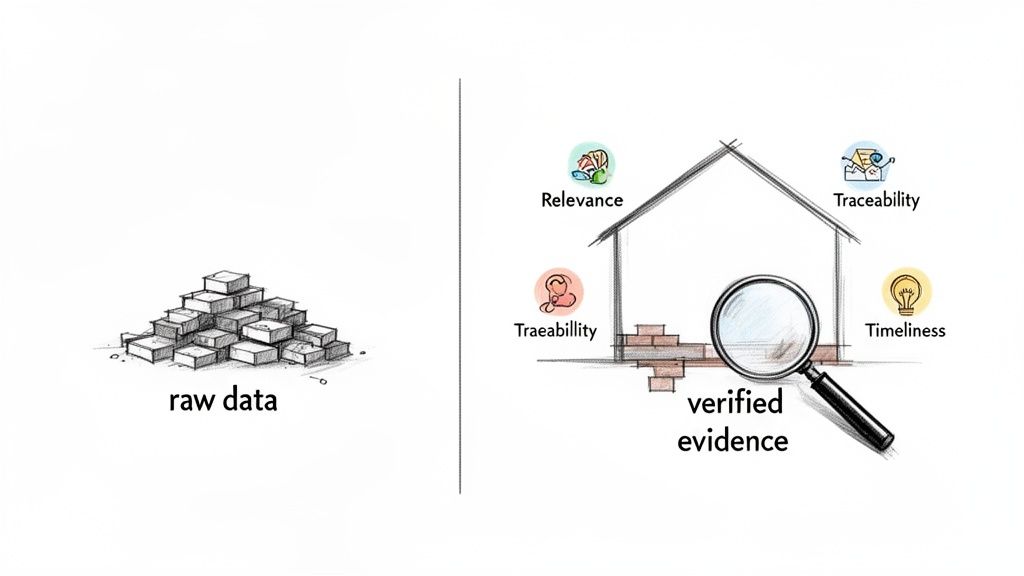

Many professionals mistakenly equate raw data or documentation with audit evidence. A policy document, a system log, or a screenshot are merely inputs. They only become evidence when their context, integrity, and connection to a specific control requirement are established and verified. For example, a server configuration file is data; that same file, linked to an approved change request, a successful post-implementation test, and access logs showing authorized deployment, becomes robust audit evidence.

For information to qualify as audit evidence, it must possess several core properties. Auditors evaluate the information provided against these standards to assess its sufficiency and appropriateness.

- Relevance: The evidence must have a direct and logical connection to the specific control or assertion being tested. Evidence of a successful disaster recovery test, for instance, is not relevant to an audit of employee onboarding controls.

- Reliability: The source and nature of the evidence must be trustworthy. System-generated logs from a secured, immutable source are inherently more reliable than a manually maintained spreadsheet, which can be easily altered.

- Traceability: A clear audit trail must exist for the evidence itself, demonstrating its origin, chain of custody, and integrity. An auditor must be able to verify that the evidence has not been tampered with since its creation.

- Timeliness: The evidence must be current and relevant to the specific period under review. Evidence from a previous audit period is generally insufficient to prove a control's current operating effectiveness.

It is critical to distinguish between evidence, documentation, logs, and attestations. Documentation, such as policies and procedures, describes intended operations. Logs are raw, time-stamped records of system events without inherent context. Attestations are statements of confirmation from individuals. Audit evidence is the curated synthesis of these and other elements that collectively and verifiably proves a control is functioning as intended.

Why Audit Evidence Is Critical in Modern Compliance

In today's regulatory environment, simply "having documents" is no longer sufficient to pass an audit. The shift towards continuous oversight and frameworks like DORA and NIS2 means that audits are evolving into ongoing processes of verification, not annual events. High-quality audit evidence is the foundation of this new model.

This evolution places the burden of proof squarely on the organization being audited. It is no longer enough to claim a control is in place; the organization must provide objective, verifiable proof of its consistent and effective operation throughout the audit period. This requirement for demonstrable accountability is central to modern governance. Without a systematic approach to managing audit evidence, an organization cannot meet this burden and exposes itself to findings, fines, and reputational damage. Strong evidence demonstrates that compliance is an embedded operational discipline, not a last-minute project. Under regulatory scrutiny, a well-managed body of audit evidence is the primary defense, transforming subjective claims into objective, verifiable facts.

Types of Audit Evidence

Auditors rely on several categories of evidence to form a comprehensive conclusion about the effectiveness of a control environment. A mature compliance program must generate and manage evidence across all relevant types to provide a complete and convincing picture. Each type serves a distinct purpose in demonstrating that controls are not only designed correctly but are also operating consistently.

Documentary Evidence

Documentary evidence establishes intent and formalizes governance. It includes the policies, procedures, standards, and reports that define how an organization intends to operate. This evidence proves that a formal management system is in place and that responsibilities have been defined. Examples include an approved Information Security Policy for an ISO 27001 audit, a formal risk assessment methodology, or a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) as required by GDPR. While essential, documents alone only prove that a plan exists, not that it is being executed.

Technical Evidence (logs, configurations, access records)

Technical evidence consists of system-generated data that provides direct proof of how controls are configured and operating. This form of evidence is often considered highly reliable because it is machine-generated and less susceptible to manual alteration. Examples include firewall configuration exports, immutable access logs from a central identity provider, vulnerability scan reports, or system settings from a cloud environment. For an auditor, reviewing the live firewall rule set is more persuasive than simply reading the network security policy.

Process Evidence

Process evidence demonstrates that a documented procedure has been consistently followed in practice. It bridges the gap between documentary evidence (the "what") and technical evidence (the "how"). This category includes records of operational activities, such as completed change management tickets with all required approvals, signed-off user access review reports, or minutes from an incident response post-mortem meeting. For instance, to prove an access review control, an organization would need the access control policy (documentary), a list of current user permissions (technical), and the quarterly review records signed by department heads (process).

Third-Party Evidence

Third-party evidence is generated by an independent external entity and is used to verify controls related to suppliers, vendors, and service providers. In an interconnected environment, managing supply chain risk is critical, and this type of evidence demonstrates due diligence. Common examples include a SOC 2 Type II report from a cloud hosting provider, a certificate of ISO 27001 compliance for a key software vendor, or the report from an external penetration testing firm. This evidence confirms that an organization's security and compliance standards extend to its partners.

Common Problems in Audit Evidence Management

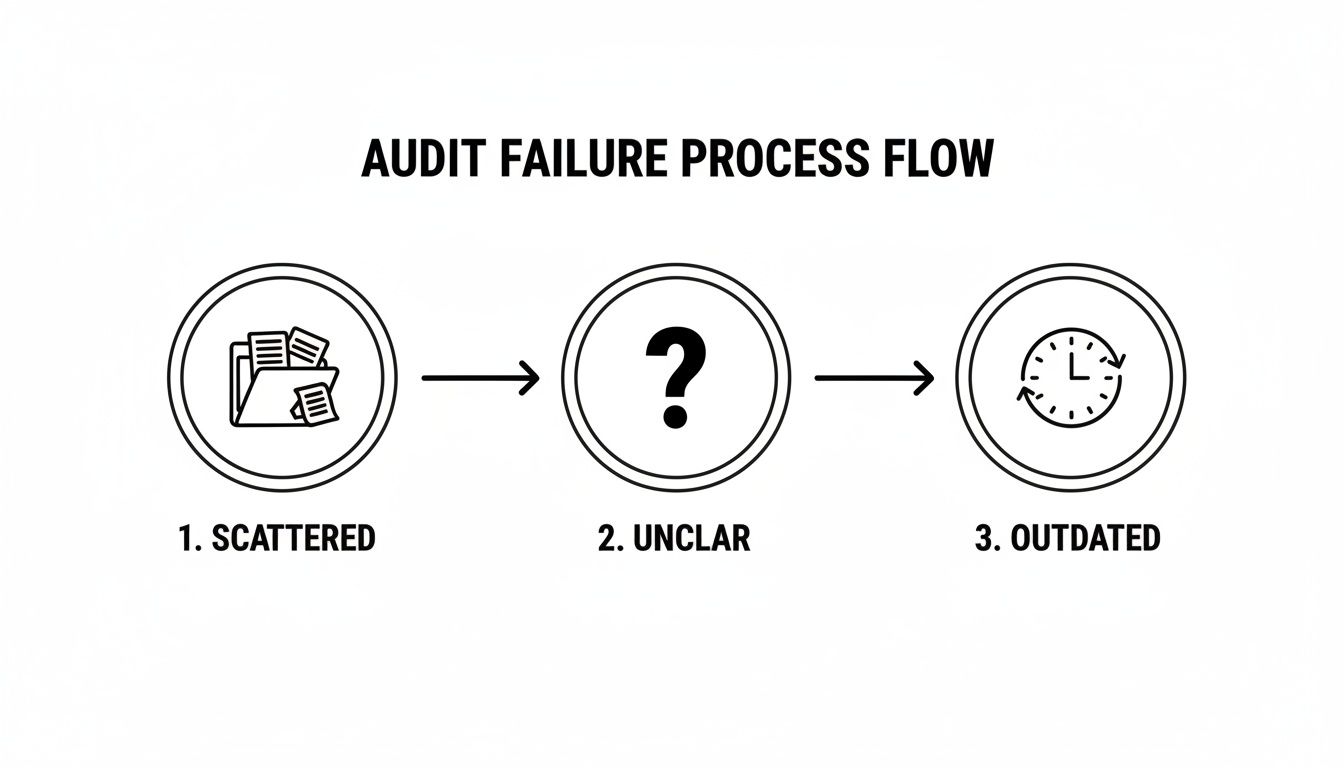

Many organizations struggle with audit evidence management not because they lack controls, but because their processes for gathering and presenting proof are fundamentally broken. From an auditor's perspective, these operational mistakes are common and immediately signal a reactive, immature compliance posture. The root cause is typically treating evidence collection as a project to be completed before an audit, rather than as a continuous operational function.

The most frequent failure is having evidence scattered across email inboxes, personal network drives, and various ticketing systems. This disorganization makes it impossible to establish a clear chain of custody, leads to inconsistent or incomplete submissions, and forces a frantic, last-minute search when an auditor requests proof.

Another critical issue is the absence of clear ownership and responsibility. When no single individual is accountable for maintaining the evidence for a specific control, it inevitably becomes outdated or goes missing. An auditor's request for evidence is met with internal confusion, delaying the audit and eroding confidence.

Reusing evidence from previous audits without proper validation is a serious error. An auditor needs proof of a control's effectiveness during the current audit period. Submitting a server configuration file from last year is not only irrelevant but also undermines the credibility of all other evidence provided.

Finally, many organizations fail to maintain a complete audit trail for the evidence itself. Without a traceable history showing who provided the evidence, when it was collected, and how its integrity has been maintained, the evidence is merely an assertion. An auditor cannot trust it as verifiable proof. These operational gaps create significant risk and often lead directly to audit findings or non-conformities.

How to Manage Audit Evidence Effectively

Effective audit evidence management is an engineering and governance discipline, not a documentation task. The goal is to design a system where reliable, verifiable proof is a natural and continuous output of daily operations. This systematic approach eliminates the last-minute, high-stress scramble that characterizes many audit preparations. It requires treating evidence management as a core operational function.

The foundational principle is centralization. All audit evidence should reside in a single, controlled repository. This eliminates the chaos of scattered information and establishes a single source of truth for control owners, management, and auditors. Centralization is non-negotiable for ensuring evidence integrity, managing access control, and providing a coherent view of the compliance posture.

Next, every piece of evidence must be mapped directly to one or more specific controls or regulatory requirements. This creates a clear, traceable link from policy to proof. When an auditor selects a control, the system should immediately present all relevant and current evidence. This structure prevents ambiguity and demonstrates a deliberate, organized approach to compliance.

Evidence is dynamic, so the system must enforce strict versioning. An auditor needs to verify a control's state during the audit period, not just its current state. Each piece of evidence must have a clear owner who is accountable for ensuring its accuracy and timeliness. This assignment of ownership and accountability eliminates confusion and ensures that evidence is actively managed.

Finally, the management system itself must maintain a complete, action-level audit trail. Every interaction with a piece of evidence—its upload, review, or replacement—must be logged immutably. This meta-evidence proves the chain of custody and integrity of the primary evidence, providing the auditor with confidence that the information presented is trustworthy and has not been tampered with.

Audit Evidence Across Compliance Frameworks

While compliance frameworks like GDPR, ISO 27001, and NIS2 have different focuses, the underlying principles of what constitutes strong audit evidence remain constant. An effective audit evidence management system allows an organization to demonstrate control effectiveness efficiently, regardless of the specific framework being audited. A single piece of technical evidence, such as a vulnerability scan report, can often serve as proof for requirements across multiple standards.

GDPR

Under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), organizations must demonstrate compliance with principles like data minimization and purpose limitation. To provide sufficient GDPR audit evidence for data retention, for example, an auditor would expect to see the approved data retention policy (documentary), system logs proving that data exceeding its retention period has been automatically deleted (technical), and records of periodic reviews confirming the policy is effective (process).

ISO 27001

ISO 27001 audits are structured around verifying the controls listed in Annex A or defined within the organization's Information Security Management System (ISMS). For a control like A.5.18, Access rights review, an auditor requires a complete evidence package: the access control policy, technical exports of current user permissions, and the signed-off records from the most recent review cycle proving that access was validated by business owners. We have a detailed guide on preparing for an ISO 9001 audit that covers similar principles.

NIS2

The NIS2 Directive emphasizes cybersecurity risk management and operational resilience. To provide adequate regulatory audit evidence for incident handling capabilities, an organization must produce its formal incident response plan (documentary), logs from security tooling (e.g., SIEM, EDR) showing detection and response actions for a real or simulated event (technical), and a post-incident report with tracked actions for improvement (process).

From Evidence Collection to Audit Readiness

There is a fundamental distinction between collecting evidence and achieving audit readiness. The former is a reactive task, often performed under pressure before an audit. The latter is a continuous operational state, the result of a well-designed system where verifiable proof is generated as a natural part of daily activities. An organization that is truly audit-ready does not need to "prepare" in the conventional sense, because the required audit evidence is always current, organized, and available.

Achieving this state requires a shift in mindset: from viewing audits as disruptive events to treating them as routine verifications of a functioning system. Effective audit evidence management is a system design problem, not a documentation problem. When an organization engineers its processes to produce reliable, traceable, and context-rich evidence by default, the audit becomes a straightforward confirmation of operational integrity. For more on this approach, read our article on compliance as a continuous system.

Audit readiness, therefore, is the ability to produce sufficient, reliable, and timely evidence for any control at any time. It is a state of perpetual preparedness built on a foundation of accountability, transparency, and operational discipline.

Audit readiness is a system design problem, not a documentation problem.