An ISO 9001 audit is not an inspection designed to uncover faults. It is a systematic process for gathering objective evidence to determine how effectively a Quality Management System (QMS) conforms to the standard's requirements. The process should be understood as a verification exercise, where an auditor confirms that the QMS operates as designed and documented.

A common mistake is to treat the audit as an examination requiring last-minute preparation. This approach creates unnecessary stress and encourages counterproductive behaviors, such as hastily assembling documents or coaching personnel on specific answers. It misinterprets the purpose of ISO 9001.

A more effective perspective is to view the audit as a system verification. The auditor's role is not to identify failures but to validate that the QMS is effective, controlled, and aligned with the organization's own policies. This reframes the audit as a collaborative review rather than an adversarial encounter, allowing the focus to shift from concealing weaknesses to presenting clear, traceable evidence of operational controls.

Shifting from an Inspection Mindset to System Verification

The primary reason to adopt a verification mindset is that it aligns the audit process with the fundamental goal of a QMS: to serve as an operational framework for the business, not merely as a certification credential. This approach reinforces the core principles of the ISO 9001 standard.

- Customer Focus: The audit verifies that defined processes consistently meet customer requirements. Evidence of feedback mechanisms and performance metrics demonstrates that this system is functioning correctly.

- Process Approach: The auditor examines the connections between activities. Demonstrating clear inputs, outputs, and ownership for each process provides evidence of operational control.

- Continual Improvement: The audit serves to confirm that the QMS is dynamic. Evidence from internal audits, management reviews, and corrective actions shows that the system is capable of learning and adapting.

Treating the ISO 9001 audit as a verification of an existing, functional system eliminates last-minute preparation. The focus shifts to demonstrating the inherent discipline of operational processes, turning the audit into a value-added activity rather than a source of organizational stress.

Ultimately, this positions the QMS as an engineering and governance discipline. The audit becomes a predictable event that validates the work performed daily by the team. It reinforces accountability and provides external confirmation that the organization's commitment to quality is operational and effective.

Defining Audit Scope and Mapping Responsibilities

A successful ISO 9001 audit depends on clearly defined boundaries. Ambiguity in the audit's scope is a common and avoidable cause of failure, leading to confusion during the audit and gaps in the presented evidence.

The scope statement is a foundational document. It specifies which processes, departments, physical locations, and product lines are covered by the Quality Management System (QMS). This is not a formality; it establishes the auditor’s expectations and provides the framework for the entire verification process. For example, a software company might scope its QMS to cover processes from client requirements gathering through to deployment and support, while explicitly excluding internal departments like HR and finance if they are governed by separate management systems. This scope must be documented, controlled, and understood by all relevant personnel.

Moving Beyond Generic Responsibility Charts

Once the scope is established, the next step is to map responsibilities. While many organizations use a standard RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) chart, this model is often too abstract for a rigorous audit. A RACI chart might assign responsibility for data backups to the "IT Department" but fail to identify the specific individual accountable for verifying backup logs each day.

An Ownership Matrix provides greater clarity. This is not a high-level organizational chart but a practical document that links specific individuals directly to the QMS controls and processes they own. It serves as a definitive directory for accountability within the system.

An effective Ownership Matrix is the difference between a smooth audit and a chaotic one. When an auditor asks, "Who authorizes production environment changes?" the matrix should provide a name, not a department. This ensures the correct individual is prepared to respond with authority.

This level of detail demonstrates to the auditor that accountability is embedded in operations, not just a theoretical concept. It prevents the delays and confusion that occur when it is unclear who should answer a specific line of inquiry.

Constructing a Practical Ownership Matrix

Building this matrix is a practical exercise focused on creating a direct link from every key QMS process to a named individual.

A functional Ownership Matrix should include:

- QMS Process or Control: A clear description of the activity (e.g., “Clause 8.5.2 - Identification and Traceability”).

- Process Owner: The single individual accountable for the process's performance and outcomes.

- Key Personnel: Other individuals who execute tasks within the process.

- Evidence Location: A direct reference or link to where objective evidence for the process is maintained.

For example, for the control "Management of Nonconforming Outputs," a generic chart might list the Quality Manager. A more effective matrix would specify the Production Supervisor as responsible for identifying and segregating nonconforming products on the factory floor, while the Quality Manager remains accountable for the overarching root cause analysis process. This distinction is vital for demonstrating granular operational control.

By meticulously defining scope and mapping responsibilities in a detailed Ownership Matrix, an organization establishes a foundation of clarity and control. This ensures every component of the QMS has a clear owner who can speak to its function and produce the required evidence on demand—the mark of a mature, well-governed system.

Systematic Evidence Collection and Management

Evidence collection for an ISO 9001 audit is not an administrative task; it is an engineering discipline that requires traceability, version control, and accessibility. The objective is to build a true evidence management system, not simply a shared folder of documents. A simple file collection lacks the structure required for a rigorous audit. An effective system provides the auditor with a clear, navigable path and demonstrates that the QMS is mature and well-controlled.

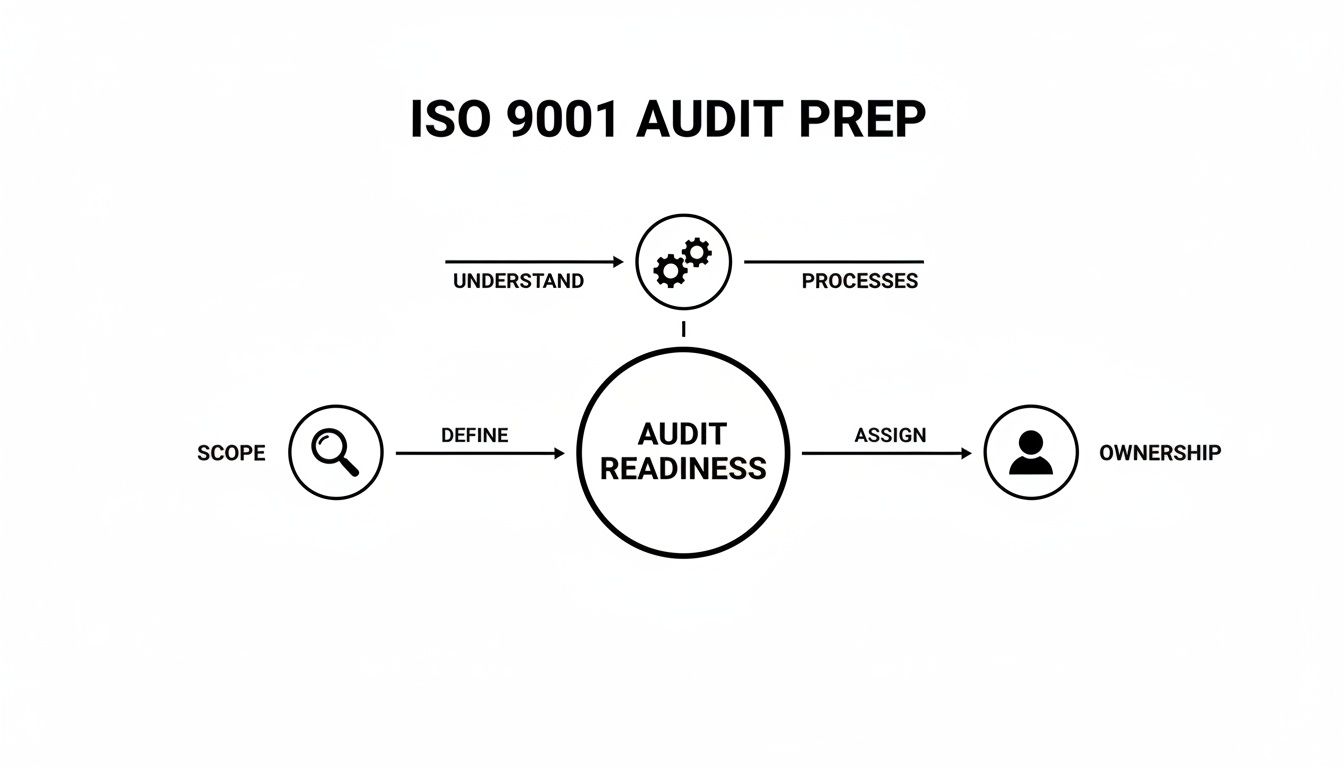

This flowchart illustrates the logical sequence for audit preparation, connecting scope, process, and ownership.

It serves as a reminder that a successful audit depends on the logical link between what the QMS covers, how its processes operate, and who is accountable for them.

Systems vs. Folders

An auditor must verify not only that a document exists but also that it is the correct, approved version that was in use during the audit period. A basic file share struggles to provide this assurance.

An evidence management system is structured to solve this problem. Each piece of evidence is treated as an object with associated metadata, such as version history, approval records, and direct links to the relevant ISO 9001 clause. This creates an auditable trail that is self-evident.

An auditor should not need to ask if a policy is the current version; the system should make it obvious. Traceability is not a feature—it is the central purpose. Effective evidence management provides immutable proof of process adherence over time.

This approach transforms evidence from a static document into a dynamic record of compliance. Instead of merely presenting a change management policy, the system can display the specific change request ticket that proves the policy was followed, complete with timestamps and digital approvals.

Linking Evidence Directly to ISO 9001 Clauses

The most practical method for organizing evidence is to map each item directly to the ISO 9001 clause it satisfies. This creates an intuitive structure that mirrors the auditor's own checklist, saving time and reducing confusion during the audit. This direct mapping demonstrates a thorough understanding of both the standard and the organization's own QMS. It proves that evidence has not just been collected, but has been systematically validated against each requirement.

- For Clause 7.1.5 (Monitoring and measuring resources), link specific calibration records, including dates, results, and the technician's identification.

- For Clause 8.3 (Design and development), link a complete project file for a recent release, from the initial requirements document to design review minutes and the final user acceptance testing records.

- For Clause 9.2 (Internal audit), provide the audit schedule, reports from completed internal audits, and the associated corrective action plans.

The following table provides examples of evidence types aligned with key ISO 9001 clauses.

Evidence Types for Key ISO 9001 Clauses

| ISO 9001 Clause | Objective | Primary Evidence Example | Secondary Evidence Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.4 Quality management system and its processes | Demonstrate that the QMS is established and maintained. | Process flowcharts and interaction diagrams for key operational flows. | Documented procedures and work instructions for each process. |

| 5.2 Policy | Show that a quality policy exists, is communicated, and understood. | The official, version-controlled Quality Policy document. | Meeting minutes or intranet posts showing its communication to staff. |

| 6.2 Quality objectives and planning to achieve them | Prove that measurable quality objectives are set and tracked. | A dashboard or report showing KPIs and progress against targets. | Project plans or action items detailing how objectives will be met. |

| 7.2 Competence | Verify that personnel are competent for their roles. | Job descriptions with required skills and training records for key staff. | Performance reviews that include an assessment of competence. |

| 8.5.1 Control of production and service provision | Confirm that processes are carried out under controlled conditions. | Production records, work orders, or service logs for specific jobs. | Checklists or sign-off sheets used during service delivery. |

| 9.3 Management review | Demonstrate that top management regularly reviews the QMS. | Official meeting minutes from management review meetings. | The presentation slides or data packs used in those meetings. |

This systematic linkage is a core function of dedicated operational evidence toolkits. You can explore the features of a system designed for this purpose.

The demand for quality and regulatory compliance is increasing across Europe. The European ISO certification market, valued at USD 3,077.5 million in 2024, is projected to grow at a 13.5% CAGR, driven by regulations such as DORA and NIS2. For technology leaders, this translates to more intensive audits and certification costs ranging from €8,000 to €40,000. This pressure makes efficient, verifiable evidence management essential. A well-organized system not only facilitates the ISO 9001 audit but also builds a strong foundation for other regulatory requirements. By treating evidence as a critical operational asset, the audit becomes a straightforward verification of existing controls.

Using Internal Audits to Drive Improvement

An internal audit is not a rehearsal for the external audit; it is a core component of the QMS continual improvement loop. Its purpose is to identify opportunities for enhancement and verify that the system functions as intended, well before an external auditor is involved. Treating it as a practice run undermines its primary function. The ISO 9001 internal audit is a proactive tool for self-correction, demonstrating that the QMS is a living system rather than a static set of documents reviewed annually.

Planning a Risk-Based Internal Audit

An effective internal audit begins with a strategic plan, not a checklist of clauses. A risk-based approach is necessary to focus time and resources on the processes that have the greatest impact on quality or customer satisfaction.

The audit plan must clearly define:

- Audit Scope and Objectives: Specify which departments, processes, or product lines will be reviewed and what the audit aims to confirm.

- Audit Criteria: This includes the ISO 9001:2015 standard itself, as well as the organization's own internal policies and process documents.

- Audit Team: Select auditors who are impartial. They must have a strong understanding of the standard and the process under review and, crucially, be independent of the area being audited to maintain objectivity.

- Audit Schedule: A timetable outlining interviews, evidence review sessions, and reporting deadlines.

This structured planning transforms the internal audit from a compliance exercise into a focused assessment of the system's health.

Executing the Audit and Gathering Findings

During the audit, the primary task is to gather objective evidence through systematic observation and verification. This involves interviewing process owners, reviewing records, and observing activities to confirm that documented procedures are being followed in practice.

The goal is not only to identify nonconformities but also to find opportunities for improvement. A finding that a process is inefficient, even if it is technically compliant, represents a valuable opportunity for optimization. For example, an internal audit might find that while every change management ticket is properly approved, the approval process itself causes significant operational delays. This is not a nonconformity, but it is a clear opportunity to improve the process without compromising control. You can learn more about structuring such processes in our article on building compliance as a continuous system.

The Role of the Management Review

The output of the internal audit serves as a primary input for the Management Review. This is the formal process through which findings are translated into action. In this meeting, top management evaluates the performance of the QMS and makes decisions regarding necessary changes.

The Management Review is the critical link between internal audit findings and meaningful improvement. It is where accountability is assigned, resources are allocated, and the organization formally commits to corrective and preventive actions.

This meeting ensures that insights from the audit are addressed. Management reviews the findings, analyzes trends, and determines what needs to change, which could involve updating a process, investing in new tools, or providing additional training. The minutes from this meeting are critical evidence for an external auditor, as they prove leadership engagement and the functionality of the improvement cycle.

The discipline of regular, rigorous internal audits is a hallmark of a mature quality system. In Germany, a major European technology hub, there are approximately 70,000 active ISO 9001 certificates. This high level of adoption, particularly in technology-intensive sectors like automotive software, underscores the value placed on systematic quality verification. You can find more insights on global ISO trends on dascertification.org. By treating the internal audit and management review as core operational disciplines, an organization builds a resilient QMS that is continuously prepared for external scrutiny.

Managing Nonconformities with a CAPA Process

It is realistic to expect that an ISO 9001 audit will identify areas for improvement. Discovering a nonconformity is not a failure; it is an expected outcome of a rigorous verification process. The organization's response to these findings is what demonstrates the maturity of its QMS. A disciplined, structured response shows that the system is capable of self-correction, which is the essence of continual improvement. It turns a finding into a positive demonstration of control.

Classifications of Audit Findings

Not all findings carry the same weight. In the closing meeting, the auditor will classify each issue, and understanding these classifications is critical for prioritizing the response.

- Major Nonconformity: This indicates a significant breakdown in the QMS, such as the complete absence of a mandatory process. A major finding could directly impact product or service quality, and certification is typically withheld until it is resolved.

- Minor Nonconformity: This represents an isolated lapse or a minor deviation from a procedure. It is not a systemic failure but indicates a weakness that needs to be addressed to prevent it from escalating.

- Observation for Improvement (OFI): This is not a nonconformity. It is a suggestion from the auditor for an area that, while compliant, could be made more efficient or less risky. OFIs are recommendations, not mandatory actions.

The immediate priority is to address any major and minor nonconformities through a formal process.

The CAPA Process: A System for Effective Remediation

The tool for this is the Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) process. This is not merely an administrative exercise but a structured problem-solving framework. Its purpose is to address the immediate issue and to identify and eliminate the underlying root cause.

A well-defined CAPA process follows a clear lifecycle. Each stage must be documented to provide the certification body with traceable evidence of resolution.

A well-executed CAPA transforms an audit finding from a point of failure into proof of a responsive, learning system. It demonstrates accountability and a commitment to resolving issues at their source, which is precisely what auditors want to verify.

A complete CAPA lifecycle consists of several distinct phases:

-

Containment: The first step is to implement an immediate correction to stop the impact of the nonconformity. For example, if defective products were shipped, this could involve a recall. This action addresses the symptom, not the cause.

-

Root Cause Analysis: This phase involves investigating why the nonconformity occurred. Techniques such as the “5 Whys” or a Fishbone diagram are used to look beyond superficial explanations. For example, a missed equipment calibration may not be due to "technician error" (the symptom) but rather to a flawed scheduling system that failed to issue a reminder (the root cause).

-

Corrective Action Planning: Once the root cause is identified, a plan is developed to eliminate it permanently. The plan must be specific, with clear owners and firm deadlines. In the scheduling example, the corrective action might be to implement a new system with automated alerts.

-

Verification of Effectiveness: After the corrective action is implemented, its effectiveness must be verified. This involves monitoring the new process over time to ensure the problem has been resolved and that no new issues have been introduced.

This entire process, from identification to verification, must be meticulously documented. This documentation serves as the objective evidence presented to the auditor to close out the nonconformity, providing tangible proof that the QMS is working effectively.

Final Preparations for a Successful Audit Day

The culmination of systematic preparation is a calm, professional audit day. This is not about last-minute cramming but about organizing the team and evidence to ensure a seamless interaction with the auditor. A smoothly executed audit day is the ultimate reflection of a well-controlled Quality Management System. The objective is to demonstrate the system's effectiveness with both confidence and clarity. This requires not only having the right evidence but also ensuring the team can engage with the auditor precisely and efficiently.

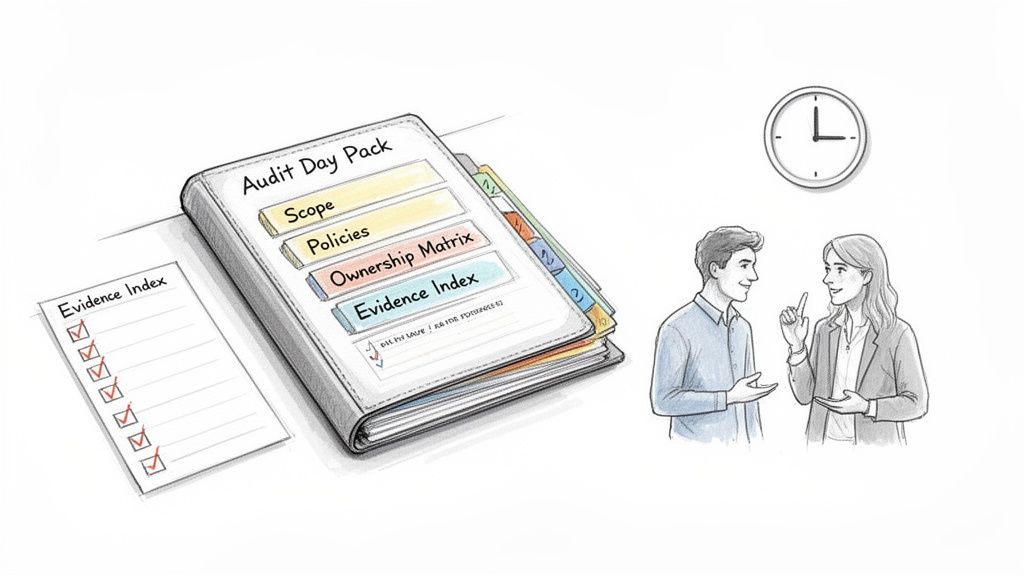

Assembling the Audit Day Pack

Respecting the auditor’s time is a powerful indicator of an organization's professionalism. The most effective way to achieve this is by preparing a comprehensive Audit Day Pack. This is not a collection of documents but a curated, indexed guide to the QMS. The pack serves as a single source of truth, allowing the auditor to quickly understand the structure and scope of the system. It prevents delays and demonstrates proactive preparation, which sets a collaborative tone from the outset.

A well-structured Audit Day Pack should contain:

- The QMS Scope Statement, which clearly defines the audit’s boundaries.

- The top-level Quality Policy, signed by senior management.

- The Ownership Matrix, mapping individuals to specific processes and controls.

- An index of all relevant evidence with direct links or references to its location.

This level of organization transforms the audit's opening meeting from a general discussion into a structured walkthrough of the system's architecture, establishing credibility immediately.

Coaching the Team for Effective Communication

How the team communicates with the auditor is as important as the evidence they present. Auditors are trained to assess not just documentation but also the real-world competence and awareness of personnel. Coaching the team is a critical final step. This is not about memorizing answers but about building confidence and ensuring everyone understands the protocols for a successful ISO 9001 audit.

The purpose of team coaching is to enable precise, factual communication. An auditor wants to hear what a process owner knows, not what they think the auditor wants to hear. Teach your team to answer the question asked, provide the requested evidence, and then stop.

Train your team on a few key principles for auditor interactions:

- Answer Directly and Concisely: If the answer is "yes," state "yes" and present the evidence. Avoid volunteering additional information or speculating, as this can open unintended lines of questioning.

- Locate Evidence Efficiently: Every process owner must know exactly where their evidence is stored and how to retrieve it quickly. Fumbling through folders undermines the perception of control.

- Articulate Their Role: Anyone interviewed should be able to clearly state their specific responsibilities within the QMS and explain how their work contributes to quality objectives.

This preparation helps ensure the audit day proceeds smoothly, free from the stress that affects unprepared organizations. It allows the discipline embedded in your system to be clearly demonstrated, turning the verification into a showcase of your commitment to quality. For more on this topic, see our guide on achieving demonstrable control.

An AuditReady operational evidence toolkit is designed to help you prepare with clarity and precision. Define scope, map responsibilities, and generate audit-ready evidence packs that demonstrate control and respect the auditor's time. https://audit-ready.eu/?lang=en