Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) is a structured, systematic approach for identifying, assessing, and managing risks that could impact an organisation's strategic objectives. It replaces a siloed approach—where individual departments manage their own risks in isolation—with a unified framework. This provides leadership with a comprehensive and consistent view of the entire risk profile, enabling more informed strategic decisions.

Enterprise Risk Management as a System, Not a Checklist

Many organisations approach enterprise risk management as a compliance-driven, box-ticking exercise. They populate risk registers, conduct an annual assessment, and file the resulting reports. This methodology is fundamentally flawed. It fails to leverage the primary purpose of ERM: to function as a continuous, dynamic system that informs strategic planning and enhances operational resilience.

A checklist is static—a snapshot in time. A system, by contrast, is dynamic. It comprises inputs, processes, controls, and feedback loops that work in concert to achieve a specific objective, such as maintaining operational stability within a defined risk appetite.

Thinking in Systems, Not Silos

Viewing ERM as a system fundamentally changes its role within the business. It evolves from a defensive administrative function into a core engineering and governance discipline. This mindset is particularly critical in regulated IT environments where security, compliance, and operational risks are interconnected.

A siloed approach to risk management creates significant blind spots. For instance, an IT security team might mitigate a technical vulnerability. Without a systemic view, however, the organisation may fail to connect that technical event to its potential impact on financial reporting integrity or compliance with regulations like DORA or NIS2.

A robust ERM system connects these disparate data points. It provides leadership with a traceable, evidence-based view of how a single risk event can propagate across the enterprise. This transforms risk management from a reactive, fragmented activity into a predictable and defensible operational capability.

The Purpose of a Formal ERM Program

The ultimate purpose of a formal ERM program is to build and maintain operational resilience. It achieves this by embedding risk-aware decision-making into the organisation's culture and operational processes. Instead of merely cataloging risks in a spreadsheet, a systems-based approach focuses on designing, implementing, and verifying the effectiveness of controls intended to mitigate those risks.

This systematic approach delivers several critical business outcomes:

- Informed Decision-Making: Leadership can allocate resources with confidence, knowing that decisions are based on a clear understanding of key risks and the verified effectiveness of existing controls.

- Predictable Operations: By systematically identifying and mitigating threats, the organisation reduces the frequency and impact of unexpected disruptions, leading to more stable and reliable performance.

- Defensible Compliance: During an audit, a well-documented ERM system serves as demonstrable proof of due diligence. It shows that risk management is an integral operational process, not a superficial afterthought. You can learn more about this concept in our guide to compliance as a continuous system.

By understanding why ERM must function as a system, organisations can move beyond mere paperwork and build a resilient framework that protects and enables their strategic objectives.

The Four Stages of the ERM Lifecycle

An effective Enterprise Risk Management program is not a reactive process for handling threats as they emerge. It is a continuous, repeatable system designed to anticipate, assess, and manage them proactively. This is typically structured as a four-stage lifecycle that systematically identifies, assesses, mitigates, and monitors risks.

This is not a one-time project but a continuous cycle that should be integrated into the organisation’s operational rhythm.

Leading frameworks such as COSO and ISO 31000 provide a common vocabulary and structure for implementing this lifecycle. While their specific terminologies may differ, the core principle is consistent: establish a formal, top-down system for managing risk. This structure is the foundation of a governable, defensible, and resilient operation.

Let's examine the ERM lifecycle through its four core stages. Each stage has a clear objective and a defined set of activities that drive the process forward.

The Four Stages of the ERM Lifecycle

| Stage | Objective | Key Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Risk Identification | To discover and document potential risks before they can affect strategic objectives. | Analyse business processes, system architectures, and third-party dependencies. Create and maintain a comprehensive risk register. |

| 2. Risk Assessment | To prioritise risks by analysing their potential likelihood and impact. | Score and rank risks (qualitatively or quantitatively). Focus resources on the most severe threats. |

| 3. Risk Mitigation | To design and implement controls that reduce risk to an acceptable level. | Decide on a treatment strategy: Mitigate, Transfer, Avoid, or Accept. Assign clear ownership for control implementation. |

| 4. Risk Monitoring | To create a continuous feedback loop that keeps the ERM system current and effective. | Review the risk landscape for new threats. Assess control effectiveness. Provide evidence that the system is working. |

This table illustrates how ERM moves from discovery to action in a logical, structured sequence. It is this systematic approach that makes the process governable and, critically, auditable.

Stage 1: Risk Identification

The initial stage is risk identification. This is not an informal brainstorming session but a systematic process to find and document any potential risk that could impede the achievement of organisational objectives. The scope must be comprehensive, covering business processes, system architectures, third-party suppliers, and the evolving regulatory landscape.

Effective identification requires input from personnel across all levels of the organisation, from front-line engineers to senior leadership. The primary output is a comprehensive risk register—a central log of all identified risks. Each entry must clearly describe the potential event and its context.

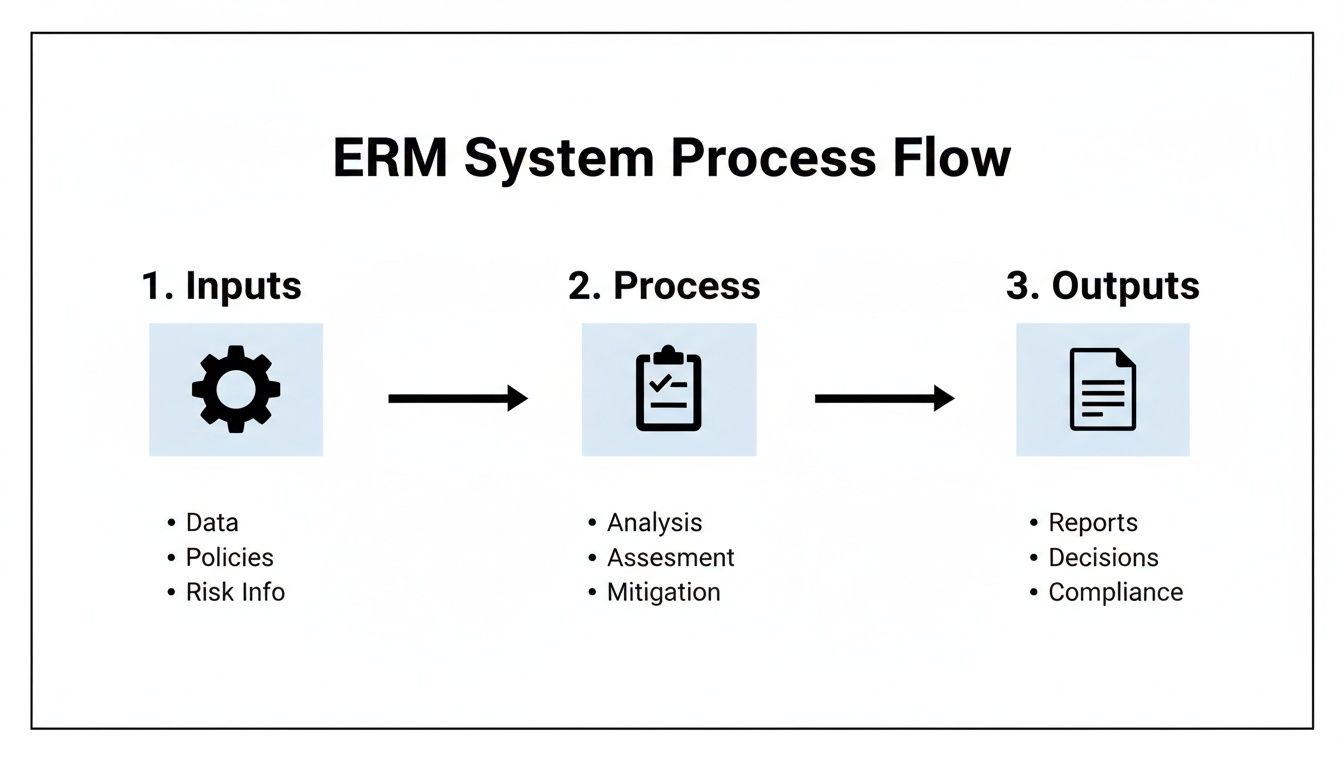

This diagram illustrates the high-level flow of an ERM system, from inputs to outputs.

This demonstrates how ERM functions as a structured process for transforming raw risk data (inputs) into actionable intelligence and auditable evidence (outputs).

Stage 2: Risk Assessment

Once risks are identified, their significance must be determined through risk assessment. This stage involves analysing two dimensions for each risk: the likelihood of its occurrence and the potential impact if it materialises. The analysis can be qualitative (e.g., high, medium, low) or quantitative (e.g., assigning financial values), but the objective is always to enable prioritisation.

This stage is critical for efficient resource allocation. By scoring and ranking risks, leadership can focus attention and investment on the threats that pose the greatest danger to the organisation, rather than treating all potential issues with equal urgency.

Stage 3: Risk Mitigation

Risk mitigation is the stage where risk analysis is translated into action. It involves designing and implementing controls to reduce a risk’s likelihood or impact to a level deemed acceptable by the organisation’s defined risk appetite. This is where high-level policies are converted into tangible operational procedures.

There are four standard strategies for treating a risk:

- Mitigate: Implement controls to reduce the risk. This is the most common approach.

- Transfer: Shift the financial impact of the risk to a third party, typically via insurance or outsourcing contracts.

- Avoid: Discontinue the activity that generates the risk.

- Accept: Formally acknowledge the risk and decide to take no action, typically when the cost of mitigation exceeds the potential impact.

Every mitigation strategy must be documented, and each control must have a designated owner to ensure a clear line of accountability.

Stage 4: Risk Monitoring

The final stage, risk monitoring, establishes the feedback loop that makes ERM a continuous cycle. It involves ongoing environmental scanning for new threats, verifying the effectiveness of existing controls, and maintaining the accuracy of the risk register. This is the stage where evidence is collected to prove that the ERM system is functioning as designed.

However, this is where many organisations falter. According to recent ERM trends from Diligent, over two-thirds of organisations face significant barriers at this stage, such as siloed teams and a lack of integrated risk data.

This presents a serious problem. While third-party breaches have doubled to 30% of incidents, only 18% of ERM leaders feel confident in their ability to identify emerging risks. This gap highlights the critical importance of a robust monitoring function for maintaining resilience in a dynamic threat landscape.

Connecting ERM to Audits Like DORA and NIS2

A robust enterprise risk management program is not merely good practice; it is the foundation of defensible compliance. For regulations like DORA and the NIS2 Directive, a mature ERM system provides the necessary structure—and evidence—to navigate an audit successfully. It transforms a potentially adversarial inspection into a straightforward verification of controls that are already managed as part of daily operations.

Auditors typically do not begin by examining a single technical configuration. They start by requesting the organisation's risk assessment. The ERM program serves as their roadmap, providing a top-down view of how the organisation identifies and manages its risk landscape. This helps them understand the why behind specific security controls.

Without a formal ERM structure, responding to audit requests becomes a chaotic, reactive exercise. Teams scramble to locate documents, justify historical decisions, and construct a compliance narrative after the fact. A functional ERM system prevents this by integrating evidence collection into routine operations.

Turning ERM Activities into Audit Evidence

The connection between ERM activities and audit preparation is direct and practical. Auditors for regulations like DORA are tasked with verifying that an organisation can withstand, respond to, and recover from ICT-related disruptions. The evidence required to demonstrate this resilience is a direct output of a healthy ERM lifecycle.

Consider these direct linkages:

- Third-Party Risk Management: DORA places heavy scrutiny on risks originating from ICT third-party providers. An ERM program’s supplier risk assessments, contract reviews, and ongoing monitoring activities produce the precise documentation an auditor requires.

- Incident Response Planning: A mature ERM system identifies operational disruption as a key risk and mandates an incident response plan as a mitigating control. The documented plan, combined with records of tests and post-incident reports, serves as direct evidence of preparedness.

- Control Testing: The "monitoring" phase of the ERM lifecycle involves testing the operational effectiveness of controls. The results of these tests—such as penetration test reports, vulnerability scan outputs, or internal reviews—are the objective evidence auditors seek.

This is not a theoretical exercise. Cyber risk has been the top enterprise risk management concern for three consecutive years, with 37% of risk managers citing it as their primary worry. With nearly 75% of companies experiencing at least one critical risk event in the past year—predominantly cyberattacks or IT failures—regulators demand demonstrable proof of resilience. More details are available in these risk management statistics on secureframe.com. For CISOs, leveraging ERM to provide this evidence is a core responsibility.

Viewing Audits as System Verification

When ERM is positioned as the core of governance, an audit becomes a less contentious event. It is no longer a subjective test to be passed or failed. Instead, it becomes an objective verification that the system the organisation claims to operate is functioning as designed.

An auditor's primary question is not "Are you secure?" but rather "Can you prove you are managing risk according to your own policies?" A well-maintained ERM program provides a clear, logical, and evidence-backed answer.

This mindset is powerful. It aligns the daily work of risk management directly with the work required for audit preparation, shifting the focus from last-minute sprints to a state of continuous readiness.

The key is establishing a clear, traceable line from a high-level policy, to a specific risk, to an implemented control, and finally, to the evidence that proves the control is effective. Building a system to manage this traceability is fundamental. You can learn more about how to achieve demonstrable control for NIS2 in our guide. This systematic approach defines modern compliance.

Establishing Clear Roles and Responsibilities in ERM

An ERM system's effectiveness is determined by the people who operate it. Technology can support the process, but it cannot replace clear ownership and accountability.

A well-established model for structuring these duties is the Three Lines of Defense. This model provides a simple but effective separation of functions, ensuring that risk management is an integrated responsibility with appropriate checks and balances.

This structure avoids the common failure mode where risk, being everyone’s responsibility, becomes no one's. It establishes a clear hierarchy for risk ownership, oversight, and independent assurance.

The First Line: Business and IT Operations

The first line of defense consists of the teams and individuals who own and manage risks directly as part of their day-to-day responsibilities. This includes engineers, product managers, and department heads whose operational decisions create or mitigate risk.

Their role is to identify, assess, and control risks within their specific domains, operating within the organisation's established risk appetite. They are responsible for implementing and operating controls effectively. Accountability for risk mitigation resides here.

The Second Line: Risk Management and Compliance Oversight

The second line of defense provides independent oversight of the first line. Its function is not to own risks but to ensure that the first line is managing them effectively. This is the domain of dedicated risk management, compliance, and information security functions.

These teams develop the frameworks, policies, and standards that the first line must adhere to. They challenge assumptions, monitor risk levels, and ensure that risk management practices are consistent across the organisation.

The second line functions as a governance body. It provides objective oversight, verifies the first line’s risk management activities, and provides leadership with assurance that the overall ERM system is operating as designed.

Key responsibilities include:

- Framework Development: Designing the ERM framework, policies, and procedures.

- Monitoring and Reporting: Aggregating risk data from across the business to provide senior management with a consolidated view.

- Expertise and Guidance: Serving as subject matter experts, providing the tools and knowledge the first line needs to execute its responsibilities.

The Third Line: Independent Assurance

The third line of defense is the internal audit function. It provides the highest level of objective, independent assurance to the board of directors and senior leadership.

Unlike the first two lines, internal audit does not participate in day-to-day risk management activities. Instead, it periodically audits the ERM system to verify that both the first and second lines are operating effectively and in accordance with established policies. It serves as the final verification of the integrity of the ERM program.

A simple ownership matrix is a powerful tool for operationalising this structure. This document explicitly maps individuals to specific risks, controls, and policies, eliminating ambiguity. For every control mandated by a regulation like NIS2, there is a named owner responsible for its implementation and the production of evidence. This makes accountability traceable and, critically, defensible during an audit.

Building a System for Evidence and Traceability

An effective enterprise risk management program creates a clear, unbroken line of traceability from a high-level policy down to the operational evidence that proves compliance. This is not an administrative burden; it is the core discipline that makes a compliance posture defensible under audit scrutiny.

Without a systematic approach to managing evidence, even the most well-designed controls are merely unsubstantiated claims.

Scrambling to collect evidence immediately before an audit is indicative of a failed process. Evidence must be treated as a primary output of the ERM workflow. This requires building a system where evidence is collected, managed, and preserved as part of routine operations, not as a reactive, ad-hoc task.

Here, it is essential to distinguish between a tool and a system. A tool might be a secure file repository. A system is a governable process that links those files to specific policies, controls, and owners, ensuring their integrity and relevance over time.

From Policy to Proof

The objective is to create a logical path that an auditor can follow without assistance. This journey begins with a high-level policy statement and concludes with concrete, timestamped evidence demonstrating that the policy is operational.

The path is sequential and logical:

- Policy Statement: The organisation establishes a rule (e.g., “All critical systems must have a tested disaster recovery plan”).

- Control Implementation: A control is designed to enforce the policy (e.g., “A full disaster recovery test will be conducted and documented annually”).

- Evidence Collection: The output of the control is captured (e.g., the signed DR test report from Q4).

- Traceable Linkage: The evidence (the report) is explicitly linked to the control, which is in turn linked to the policy.

This linkage is what transforms a collection of documents into a defensible audit package. An operational evidence management system is essential for creating these connections and managing the lifecycle of the evidence itself. You can explore the practical aspects of managing different types of audit evidence in our guide.

A defensible compliance posture is not built on the quality of policies but on the quality of evidence proving those policies are operational. Traceability is the bridge that connects them.

This structured approach is particularly critical when managing third-party risks. For IT organisations in North America and Europe, information security risks are the top concern for 32% of ERM professionals. Furthermore, 41% of these organisations have experienced a critical risk event originating from a vendor, yet 48% continue to use spreadsheets for third-party risk management.

This manual approach is inadequate for demonstrating control, especially when platforms designed for this purpose can manage the process with secure, versioned evidence collection. You can discover more insights in the research on procurementtactics.com.

Control Evidence vs. Audit Evidence

It is also important to distinguish between the operational evidence generated by controls and the curated evidence package prepared for an audit. They are related but serve different purposes. One is an operational artifact; the other is a demonstration of compliance.

| Characteristic | Control Evidence (Operational) | Audit Evidence (Prepared) |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | To prove a control is functioning correctly at a point in time. | To demonstrate compliance with a specific requirement over a period. |

| Frequency | Continuous or periodic (e.g., daily logs, quarterly reports). | Collected and curated for a specific audit period. |

| Audience | Internal teams, control owners, system managers. | External or internal auditors. |

| Format | Often raw, technical, or fragmented (logs, screenshots, config files). | Organised, contextualised, and presented clearly. |

| Scope | Narrow and specific to a single control execution. | Broad, often covering multiple controls and evidence points. |

Understanding this distinction helps in designing a system that effectively captures operational proof while streamlining the process of assembling it for an audit.

The Hallmarks of Trustworthy Evidence

Not all evidence is created equal. To be credible to an auditor, evidence must possess certain characteristics, and the system managing it must enforce them.

Every piece of evidence must be:

- Immutable

- Versioned

- Securely stored

An immutable audit trail is a non-negotiable requirement. This means that every action related to an evidence artifact—upload, access, modification, deletion—is recorded in an append-only log that cannot be altered. This gives auditors confidence in the integrity of the evidence presented.

Clear version control is equally important. Policies, systems, and controls evolve. An evidence management system must be able to demonstrate not only the current state but also the state during a previous audit period, proving consistent management over time.

Finally, secure, encrypted storage with role-based access control is fundamental. It protects the confidentiality and integrity of sensitive evidence and ensures that only authorised individuals can access or manage it.

Common ERM Pitfalls and How to Sidestep Them

Even a well-designed enterprise risk management program can fail in implementation. Success depends less on the elegance of the framework and more on avoiding common pitfalls that turn a dynamic system into a static, bureaucratic exercise. Identifying these traps is the first step toward building an ERM system that delivers genuine resilience.

One of the most frequent mistakes is treating ERM as a one-time project. A team conducts an initial risk assessment, populates a register, and then archives it until the next audit cycle. This approach misses the fundamental point. The risk landscape is not static; therefore, the ERM system cannot be. It must be a living process that adapts to new threats, business changes, and evolving regulatory requirements.

Focusing on Documentation Over Outcomes

Another common failure is allowing the process to become focused on producing artifacts rather than reducing risk. The objective is not to create a perfect risk register or a beautifully formatted policy document. The objective is to implement effective controls that demonstrably reduce the organisation's exposure to threats.

The success of an enterprise risk management system should be measured by its impact on operational stability and defensibility, not by the volume of its documentation. An ERM program is a means to an end—resilient operations—not an end in itself.

This pitfall often leads to ambiguous ownership. A risk is logged in a central repository, but because no single individual is accountable for implementing and monitoring the associated controls, accountability diffuses and ultimately disappears.

Mistaking a Tool for a System

Perhaps the most significant pitfall is the belief that a GRC tool will, by itself, solve the ERM challenge. A tool can support a process, but it is not a substitute for the process. Procuring software without a well-defined underlying system of governance, ownership, and accountability is a recipe for expensive failure. A tool cannot define an organisation's risk appetite, assign ownership, or cultivate a culture of risk awareness.

To avoid these common failures, organisations should:

- Define the Process First: Design the ERM lifecycle, roles, and responsibilities before evaluating technology. The tool must be selected to support the established system, not dictate it.

- Enforce Clear Accountability: Use a simple ownership matrix to map every control to a named individual. Ambiguity is the enemy of effective risk management.

- Adopt an Engineering Mindset: Treat ERM as a technical and governance discipline. Build a continuous feedback loop where monitoring informs assessment, and mitigation effectiveness is continuously verified.

By understanding these common traps, leaders can architect an ERM system that is dynamic, accountable, and evidence-based—one that drives informed decisions and delivers demonstrable resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions About Enterprise Risk Management

The following are common questions about implementing a practical enterprise risk management program, with answers focused on what works in regulated IT environments where evidence of control is paramount.

How Is ERM Different From GRC?

ERM (Enterprise Risk Management) and GRC (Governance, Risk, and Compliance) are often used interchangeably, but they are distinct concepts.

GRC is the overarching framework of capabilities that enables an organisation to operate ethically, manage its affairs, and meet its regulatory obligations. ERM is a specific, critical component within that broader GRC framework. It is the systematic process that identifies, assesses, and manages threats to the organisation's strategic objectives.

In essence, GRC sets the overall strategy for how the organisation is governed, while ERM is the operational engine that executes the risk management component of that strategy. ERM provides the risk-related data and evidence that the GRC function needs to make informed governance decisions.

What Are the First Steps for an SME to Establish ERM?

For a small or medium-sized enterprise, the first steps in establishing an ERM program are centered on governance and strategy, not technology.

- Assign Ownership: Designate a single individual who is accountable for the ERM program. This person does not need to be dedicated full-time, but clear ownership is non-negotiable. Without it, the initiative will fail.

- Define Risk Appetite: The leadership team must formally agree on the types and levels of risk the organisation is willing to accept in pursuit of its objectives. This statement provides the strategic boundaries for all subsequent risk management activities.

- Create a Risk Register: Begin with a simple, centralised risk register to document identified risks. Focus initially on the top 10-15 risks that pose the most significant threat to key business objectives. Avoid the temptation to identify every conceivable risk at the outset.

This foundational work establishes the necessary human systems and strategic alignment. Technology should be considered only after these elements are in place.

How Can We Measure ERM Effectiveness Objectively?

Measuring ERM effectiveness is not about the subjective colour-coding of a risk heat map. Objective measurement is based on evidence and answers a single question: are our controls operating effectively?

An effective ERM program is not one with the lowest number of identified risks; it is one with the highest quality of evidence demonstrating that its controls are operating as designed.

To measure ERM effectiveness objectively, track metrics such as:

- Control Test Success Rate: What percentage of critical controls passed their most recent scheduled test? This is a direct, quantitative measure of control effectiveness.

- Audit Finding Reduction: Track the number and severity of internal and external audit findings over time. A consistent downward trend is a strong indicator of a maturing ERM program.

- Mean Time to Respond/Recover (MTTR): Measure the time it takes to detect, respond to, and recover from operational incidents. Improvements in these metrics are a direct result of effective risk management and increased resilience.