A cyber risk strategy and governance framework provides the structure for defending an organisation’s digital assets. The strategy is the long-term plan that links security activities to business objectives. Governance is the system of policies, roles, and processes that ensures the strategy is implemented and accountability is maintained.

Understanding Core Principles

A common misstep is to view cyber risk strategy and governance as a single compliance exercise. They are two distinct but interconnected disciplines.

Strategy defines the 'why'—the desired outcome. Governance provides the 'how'—the system of controls and responsibilities to achieve that outcome.

Without a clear strategy, governance activities lack purpose. Without governance, a strategy remains an abstract plan with no mechanism for execution or verification. This distinction is critical for CISOs and IT managers. Daily operational tasks, such as patching servers or configuring firewalls, are security operations, not strategy. Strategy involves higher-level decisions, such as identifying the organisation’s most critical assets and defining the level of risk the business is willing to accept.

Strategy: The 'Why'

The strategy answers foundational questions about the approach to cybersecurity. It connects technical security objectives to business outcomes, ensuring resources are directed toward protecting assets critical to the organisation's mission.

A functional strategy is not a list of security tools. It is a deliberate plan that addresses:

- Business Objectives: How will security support business growth and innovation rather than impede them?

- Risk Appetite: What level and type of risk is the board and senior leadership willing to accept to achieve strategic goals?

- Threat Landscape: What are the credible threats to the organisation and its industry sector?

Governance: The 'How'

Governance translates strategy into a structured, auditable system. It is an engineering discipline focused on establishing clarity, assigning responsibility, and producing verifiable evidence.

Effective governance is not about achieving a perfect audit score; it is about building a defensible system that operates predictably. For a deeper look, you can learn more about how this connects to enterprise risk management.

Governance provides the framework for accountability. It ensures that when a control is implemented, there is a clear record of who is responsible for its operation, how its effectiveness is measured, and what evidence confirms it is working as designed.

This system provides the structure required for operational resilience. It establishes policies, defines roles and responsibilities, and implements reporting mechanisms that enable leadership to oversee risk without being consumed by technical details.

To clarify this distinction, the following table provides a breakdown.

Strategy vs. Governance: Key Distinctions

| Aspect | Cyber Risk Strategy | Cyber Risk Governance |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Defines the organisation's long-term security vision and direction. | Implements the strategy through a system of rules and accountability. |

| Focus | Why specific assets are protected and what the objectives are. | How security activities are executed, measured, and reported. |

| Timeframe | Long-term (3-5 years), reviewed periodically. | Continuous, operational, and cyclical (e.g., annual reviews). |

| Key Question | "Are we doing the right things?" | "Are we doing things right?" |

| Output | A risk-based plan aligned with business objectives. | Policies, standards, roles, metrics, and auditable evidence. |

| Ownership | C-suite, Board of Directors, CISO. | CISO, Risk Committee, Control Owners, Internal Audit. |

Strategy sets the direction, while governance ensures the organisation stays on course, operates correctly, and can provide evidence of its processes. Both are indispensable.

Building a Modern Governance Framework

A functional cyber risk strategy is more than a document; it is a clear, defensible system for managing security operations. This is not about generating paperwork, but about connecting the board's high-level business objectives directly to the technical controls implemented on systems. Its success depends on clarity, accountability, and the ability to produce verifiable evidence.

The entire framework is anchored by a single, critical element: the risk appetite statement.

This is a concise declaration from the board that defines the amount and type of risk the organisation is willing to accept. It translates abstract concepts of risk tolerance into concrete boundaries for decision-making. It ensures every security investment and operational choice aligns with leadership's defined parameters.

This statement is the top-level directive from which all other governance components flow. It provides CISOs and IT managers with the authority to make risk-based decisions, confident they are operating within approved limits.

Establishing a Clear Policy Hierarchy

Once the risk appetite is defined, it must be cascaded down through a structured policy hierarchy. This ensures every control has a clear line of traceability back to a business requirement, eliminating arbitrary practices.

A functional hierarchy is structured as follows:

- Policies: Broad statements of intent that reflect the organisation's risk appetite. For example, a policy might state that all sensitive customer data must be encrypted.

- Standards: Mandatory rules that specify how policies will be implemented. A standard would mandate the use of AES-256 encryption to meet the policy requirement.

- Procedures: Step-by-step instructions for implementing a standard. A procedure would detail the exact process for configuring a specific database server to use AES-256.

This structure connects a technical configuration setting all the way back up to a strategic, board-level decision.

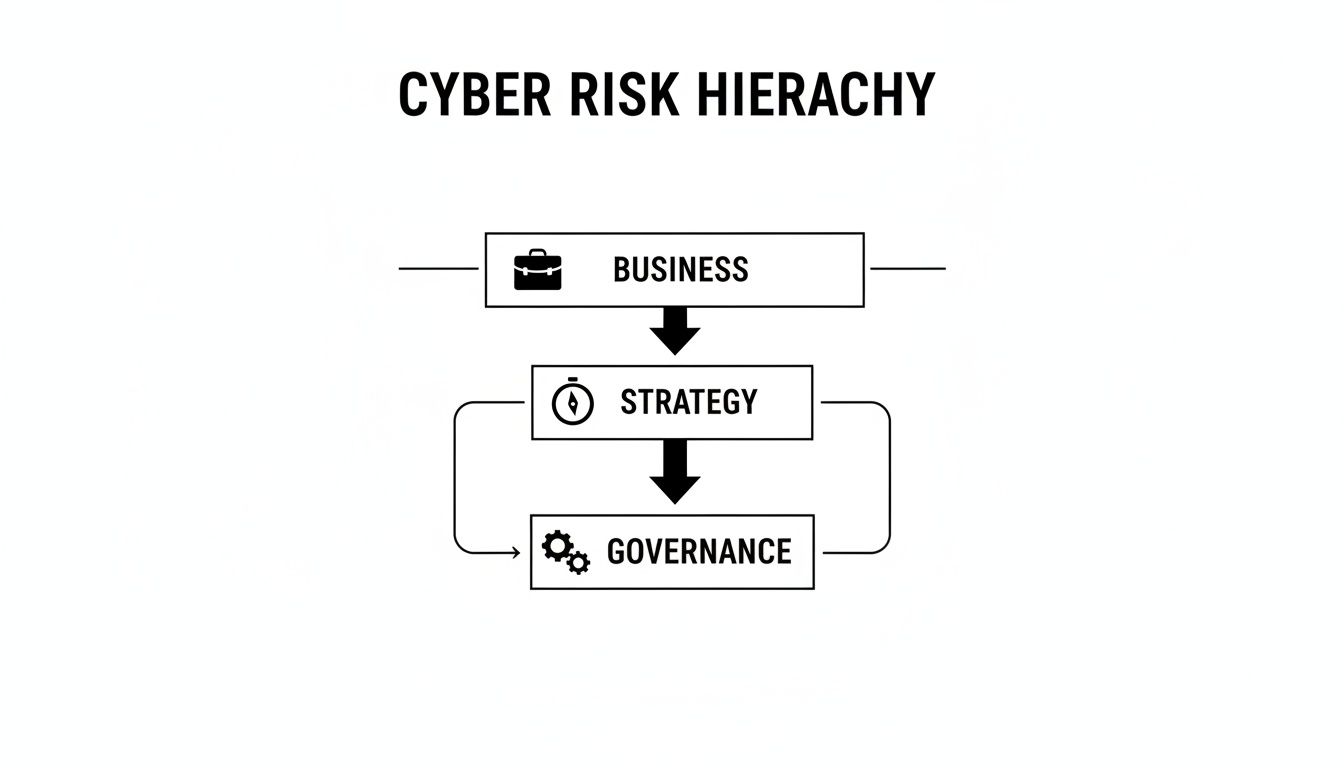

The following diagram shows how business objectives inform strategy, which is then executed through this structured governance model.

This illustrates that governance is not an isolated compliance function but the operational engine that translates strategy into action.

Assigning Unambiguous Accountability

Effective policies require clear ownership. An Ownership Matrix—often implemented as a RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) chart—is an essential tool. It assigns unambiguous responsibility for every control, preventing the confusion and blame-shifting that often occurs during an incident.

For a control such as "Quarterly User Access Reviews," the matrix specifies who is Accountable for its completion, who is Responsible for performing the work, and who must be kept informed. This simple act transforms governance from a theoretical concept into an operational reality.

The consequences of failing to establish clear accountability are significant. The IMF has reported that extreme cyber loss events have quadrupled since 2017 to approximately $2.5 billion. For the smaller businesses where 46% of breaches occur, the stakes are even higher. Systems providing tools like TOTP 2FA and immutable logs are no longer optional; they are critical for linking policies to provable controls. You can review recent cybersecurity statistics and insights for more context.

Measuring What Matters with Key Risk Indicators

A mature governance framework is data-driven. Key Risk Indicators (KRIs) are forward-looking metrics that serve as an early warning system, helping leaders identify potential issues before they escalate into incidents.

A KRI is not a measure of performance but an indicator of risk. For instance, "percentage of servers patched within 30 days" is a Key Performance Indicator (KPI). The corresponding KRI would be "percentage of critical servers with unpatched vulnerabilities older than 30 days."

Effective KRIs must be:

- Relevant: Directly linked to the risks defined in the risk appetite statement.

- Measurable: Based on reliable, collectible data.

- Predictive: An indicator of a potential future problem, not a past failure.

- Actionable: A threshold breach should trigger a predefined response.

Focusing on a small number of meaningful KRIs provides leadership with the concise, decision-useful information needed to manage risk proactively. This approach transforms the governance framework from a static set of rules into a dynamic system for building operational resilience, proving that controls are not only implemented but also effective.

Mapping Governance to Regulatory Requirements

A strong internal governance framework is the foundation of operational resilience. It must also satisfy external regulatory demands.

Regulations like DORA, NIS2, and GDPR should not be treated as separate compliance challenges. They are external expressions of the same core principles—risk management, due care, operational integrity—that a robust governance system should already embody.

The key is to shift from treating compliance as a separate checklist for each regulation to building a single, centralised system of internal controls. This approach eliminates redundancy and establishes a single source of truth for demonstrating compliance across multiple frameworks.

The Principle of Control Mapping

Control mapping is the practice of linking a single, well-defined internal control to the multiple regulatory requirements it helps satisfy.

For example, an internal control such as "Quarterly User Access Reviews for Critical Systems" is more than an internal best practice. It is a single activity that provides direct evidence for several regulatory mandates:

- NIS2: It demonstrates a concrete measure to secure network and information systems.

- DORA: It helps fulfill requirements for ICT access control policies.

- ISO 27001: It aligns with controls such as A.5.15 (Access Control) and A.8.2 (Privileged Access Rights).

- GDPR: It supports the principle of data minimisation by ensuring access to personal data is restricted as required.

The control is designed once and mapped to every applicable requirement. This creates an efficient, scalable, and defensible compliance system. The objective is no longer to chase individual regulatory articles but to strengthen the core integrity of operations.

Developing a Central Control Library

A central control library is the foundation for this approach. This is not just a list of security tools, but a curated catalogue of the specific processes, technical configurations, and administrative actions the organisation uses to manage risk.

Each control in the library should be described in clear, framework-agnostic terms. It must define the control's objective, implementation method, owner, and the evidence it produces. Once defined, that single control can be linked to any number of external requirements.

This methodology transforms compliance from a reactive, audit-driven activity into a proactive, evidence-based discipline. The goal is a system where compliance is the natural, continuous output of well-governed operations. You can learn more about generating the right kind of proof by understanding what makes a demonstrable control under NIS2.

An audit should not be an inspection that disrupts operations. It should be a routine verification of a system that is designed to be continuously verifiable. A central control library with clear mappings makes this possible.

When a new regulation is introduced, the process does not start from scratch. The task does not start from scratch. The task becomes a gap analysis: review the new requirements against the existing control library, identify any gaps, and create or update controls as needed.

This methodical process ensures the governance framework remains resilient and adaptable. An audit is no longer a test of memory or last-minute preparation; it becomes a validation of the system's documented design and its operational evidence.

Implementing an Ownership-Driven Governance Model

A documented governance framework is a plan. An operational governance system is a reality. The transition from plan to reality depends on a single concept: ownership.

An ownership-driven model is not about assigning blame. It is about building a system where accountability drives execution, measurement, and improvement. Without clear responsibility, even the best-written policies are merely documents; they do not control organisational behaviour.

The implementation process begins with people, not technology. It requires buy-in from department heads, IT leaders, and business unit managers who must understand and accept their roles in a shared-responsibility model for security. The first phase is about building consensus for a gradual, manageable rollout.

Defining Roles With an Ownership Matrix

The core of this model is the Ownership Matrix. It is a practical tool for assigning accountability, typically implemented as a RACI chart (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed). Its primary value is its clarity. For every control, policy, and process, the matrix states exactly who is assigned to each role.

This act of assignment eliminates ambiguity and creates a clear map of responsibilities.

- Accountable: The single individual with ultimate ownership for the task's completion. There can only be one ‘A’.

- Responsible: The person or team performing the work.

- Consulted: Subject matter experts who provide input before a decision or action.

- Informed: Individuals who are updated on progress or outcomes.

This structure translates abstract principles into concrete responsibilities. For a process like "Incident Response Testing," every participant knows their role—from the CISO who is Accountable to the IT Manager who is Responsible for executing the test.

Here is a simplified example of how this applies to a key governance process.

Example Ownership Matrix for Incident Response

This table illustrates how a RACI chart assigns clear responsibilities for 'Incident Response Testing' across different roles, ensuring no ambiguity.

| Task/Process | CISO | IT Manager | Compliance Officer | Business Unit Head |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plan and scope test scenarios | A | R | C | C |

| Execute technical testing | I | A/R | I | I |

| Document findings and gaps | I | R | A | C |

| Approve remediation plan | A | C | C | R |

| Report results to leadership | A | C | I | I |

By mapping responsibilities in this manner, guesswork is removed. The matrix becomes a single source of truth for ownership, making governance operational rather than theoretical.

Phased Implementation and Gap Assessment

Attempting to implement an entire governance framework at once often creates resistance. A phased approach, beginning with a gap assessment, is more effective. This involves comparing current controls and processes against the target state defined by policies and regulations.

A gap assessment is a diagnostic, not an audit. It is designed to identify missing controls, unclear ownership, and weak processes in a constructive manner. The output is a prioritised roadmap that directs teams to focus on the most critical areas first, such as securing sensitive data or hardening critical infrastructure.

The need for this structured approach is evident in the current threat landscape. Reports indicate a 48% increase in ransomware, and breaches involving cloud data now feature in 82% of incidents in some studies. For organisations subject to regulations like DORA, these figures underscore the need for operationally sound governance. To get a fuller picture, you can explore the latest cyber risk statistics and trends.

Establishing Repeatable Processes

With ownership defined and priorities established, the final step is to build repeatable processes for collecting evidence and reporting. This is what makes governance sustainable, transforming it from a series of discrete projects into a continuous discipline.

Effective governance relies on systemic repeatability. Processes for collecting evidence, reviewing controls, and reporting on risk should be as predictable and automated as possible to reduce human error and ensure consistency.

This involves designing clear procedures for how evidence is captured, stored, and tracked. It also means establishing reporting cadences for different audiences. Technical teams may require weekly updates on control performance, while the board needs a quarterly summary of Key Risk Indicators (KRIs) linked to the organisation's risk appetite.

When these processes are designed from the outset, the system becomes inherently audit-ready. Evidence generation is a natural byproduct of daily operations. When an audit occurs, the documentation is already organised, traceable, and available. The audit is no longer a disruptive event but a routine verification of an effective, ownership-driven system.

Mastering Evidence Management For Audit Readiness

A cyber risk strategy is only as robust as the evidence that proves its effectiveness. Evidence management is not an administrative task; it is an engineering discipline focused on producing a verifiable, trustworthy record that controls are operating as designed.

Without credible evidence, policies are merely statements of intent, and controls are unverified assumptions.

Strong, audit-ready evidence is specific, timely, and directly linked to a control. It is more than a simple attestation; it is a collection of artifacts that prove a control is functioning correctly.

Defining Strong Evidence

Not all evidence is of equal quality. The most defensible evidence is system-generated and difficult to tamper with, providing an objective record rather than an opinion.

Consider these examples of strong evidence:

- System-Generated Logs: Unmodified logs from firewalls, servers, or applications showing specific events, such as user access or configuration changes.

- Configuration Screenshots: Time-stamped screenshots from system interfaces that clearly display a required security setting, such as encryption being enabled.

- Signed Documents: Digitally or physically signed policy documents, risk assessments, or change requests with a clear version history.

- Tool Outputs: Reports generated by vulnerability scanners or Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) systems.

The integrity of this evidence is paramount. Systematic processes are required to maintain its credibility, such as version control for documents and the use of systems that produce immutable, append-only audit trails. This ensures the evidence presented to an auditor is the same as what was collected when the control was executed.

Systematic Evidence Collection

Effective evidence collection is not a reactive scramble before an audit; it is a continuous, operational process integrated into the daily work of control owners.

This requires establishing repeatable procedures for capturing, storing, and indexing evidence as controls are performed. When a quarterly access review is completed, the signed-off report should be immediately uploaded to a central repository and linked directly to the access review control. This systematic approach builds an ongoing library of verifiable proof.

You can learn more about what constitutes good audit evidence and its practical applications in our detailed guide.

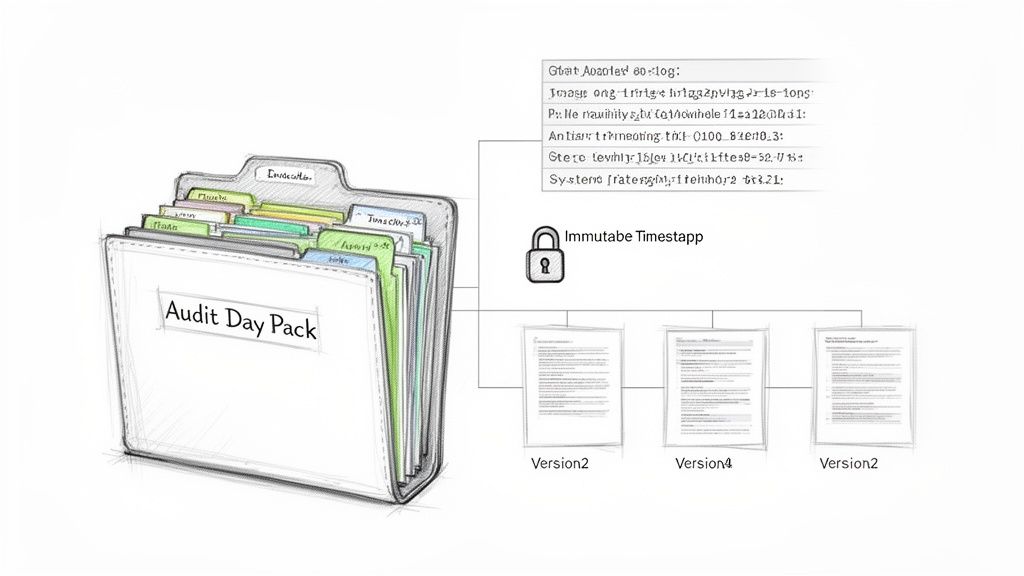

An audit should be a system verification, not an investigation. The goal is to present a curated, indexed package of evidence that lets an auditor efficiently validate that your governance system operates exactly as you've documented it.

This mindset is particularly critical for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Recent data shows SMEs are the target in approximately 50% of all cyberattacks, and 60% cease operations within six months of a significant breach.

With only 14% of SMBs reporting that they feel prepared for an attack, a significant governance gap exists. For these organisations, platforms that enable evidence versioning and directly link policies to controls are essential for becoming audit-ready.

Preparing The Audit Day Pack

The final output of systematic evidence management is the 'Audit Day Pack'. This is not a random collection of files, but a carefully curated and indexed package of evidence tailored to the specific scope of the audit.

The pack should be organised logically—often by control family or regulatory domain—making it easy for an auditor to navigate. Every piece of evidence should be clearly labelled and linked back to the specific control it supports.

This level of preparation demonstrates a mature governance process. It allows the audit to proceed as a smooth verification of an organised system, proving that controls are not only well-designed but are operating effectively, consistently, and accountably.

Sustaining Governance with Continuous Improvement

A cyber risk strategy is not a project with a fixed endpoint. A framework that is not continuously maintained will become ineffective as business objectives evolve, technology advances, and new threats emerge.

Mature governance is designed for adaptation. It is not a static document but a living system embedded in the organisation’s operational rhythm, designed to learn and improve over time. This requires building feedback loops that convert operational data into strategic adjustments.

Integrating Feedback Loops for Refinement

The engine of sustainable governance is the feedback loop. Its purpose is to use learnings from real-world tests and verifications to strengthen the framework. This is a process of systematic improvement, not blame assignment.

Key inputs for this loop are valuable sources of intelligence:

- Incident Response Simulations: Tabletop exercises and technical drills are controlled experiments. They test policies, procedures, and controls under pressure in a safe environment, revealing weaknesses before a real incident occurs.

- Periodic Gap Analyses: As the external environment changes, so must controls. A regular gap analysis compares the current security posture against new regulations or emerging threat intelligence, indicating where governance needs to evolve.

- Audit Findings: Internal and external audits provide an objective, third-party assessment of the system. Their findings should be viewed not as a grade but as a prioritised list of opportunities to improve processes and strengthen controls.

A mature governance programme doesn't just collect data—it turns it into intelligence. The results from a simulation or an audit aren't the end of a process. They are the beginning of the next cycle of improvement, ensuring the cyber risk strategy stays relevant and effective.

By feeding these insights back into policy updates, control enhancements, and training, the organisation builds resilience. This cycle of continuous improvement is the hallmark of a well-managed, defensible security programme.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Difference Between Cyber Risk Management and Governance?

Risk management is the operational activity of identifying threats, assessing vulnerabilities, and implementing controls. It is the 'doing' part of security.

Governance is the oversight framework that ensures these activities are performed correctly, are aligned with business objectives, and are fully accountable. Governance asks, "Are we managing the right risks, and can we prove it?" In essence, management executes the work, while governance ensures the work is done right.

How Can a Smaller Business Implement Robust Governance?

For smaller businesses, the objective is clarity, not bureaucracy.

Begin with the fundamentals that provide the most value. Draft a simple risk appetite statement defining acceptable risk levels. Create a core set of policies for the most sensitive operations.

Use an Ownership Matrix (e.g., RACI) to assign clear responsibilities; this creates accountability at minimal cost. Prioritise evidence collection for critical systems rather than attempting to cover everything. The goal is a lean, clear, and defensible system that demonstrates due care, not a complex administrative machine.

How Often Should a Cyber Risk Strategy Be Reviewed?

A static strategy quickly becomes irrelevant.

The overall cyber risk strategy requires a formal review at least annually. This is the minimum. A significant event—such as a merger, a new regulation, or a major shift in the threat landscape—should trigger an immediate ad-hoc review.

However, the components of the governance framework must be reviewed more frequently. Risk assessments and control effectiveness metrics should be assessed on a quarterly or semi-annual basis. This cadence provides leadership with timely data for decision-making and keeps the framework operationally relevant, preventing governance from becoming a once-a-year, check-box exercise.