FATCA and CRS reporting is the operational discipline of identifying, classifying, and reporting financial accounts held by foreign tax residents. It requires robust, auditable systems for due diligence, data aggregation, and secure information exchange with tax authorities.

The core distinction is scope: the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) is a unilateral U.S. regulation targeting U.S. persons, while the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) is a multilateral framework for tax transparency among over 100 participating jurisdictions. For a financial institution, compliance is an engineering problem: building a system that can consistently and verifiably execute these obligations.

Understanding the Foundations of FATCA and CRS

Effective FATCA and CRS reporting depends on a well-engineered system, not a compliance checklist. For compliance, risk, and IT leaders, the objective is to build a demonstrable control framework that consistently identifies, classifies, and reports the correct financial accounts under the correct jurisdiction.

These regulations were established to combat offshore tax evasion by creating a global standard for the Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI).

The U.S. initiated this standard with FATCA, which compels Foreign Financial Institutions (FFIs) to report on financial accounts held by U.S. taxpayers. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) then developed the CRS as a multilateral model for information sharing among all participating nations.

Distinguishing FATCA and CRS Scope

While the objective of both frameworks is tax transparency, their operational mechanics differ significantly. Understanding these distinctions is the first principle in designing a functional compliance system.

FATCA is a unilateral reporting regime focused on identifying "U.S. Persons" based on indicia of U.S. status, such as citizenship or tax residency. In contrast, CRS is multilateral and requires financial institutions to identify any account holder who is a tax resident in any other participating jurisdiction.

This has direct implications for system design:

- FATCA systems must be configured to detect specific U.S. indicia, such as a U.S. birthplace, address, or telephone number.

- CRS systems must be capable of processing and validating tax residency information for dozens of countries, each with unique formats for Tax Identification Numbers (TINs).

At its core, compliance is an engineering problem. The challenge is not merely to file a report, but to build a traceable, evidence-based system that can prove its own correctness under scrutiny. This means every classification, every data point, and every submission must be linked back to a defined control and a piece of verifiable evidence.

Core Definitions in Practice

The regulations use precise functional definitions. A Financial Institution (FI) is defined by its activities, not its name, and includes custodial institutions, investment entities, and certain insurance companies. An entity's obligations are determined by what it does.

Similarly, a Reportable Account is any financial account held by one or more Reportable Persons. This definition requires FIs to embed systematic due diligence into client onboarding and lifecycle management processes. It is not a single check but a continuous monitoring function, designed to detect changes in an account holder's tax residency that may trigger a reporting obligation.

Defining Your Scope and Due Diligence Obligations

Correctly defining the scope for FATCA and CRS reporting is a systematic process, not an estimation. It requires embedding due diligence controls directly into operational workflows, ensuring every client account is classified accurately from inception.

This process begins at client onboarding and persists throughout the account lifecycle. A defensible system must maintain a clear evidence trail for every classification decision, linking client self-certification forms, identity documents, and other collected data directly to the account's final status as a "Reportable Person" under either framework.

Identifying Reportable Indicia

The due diligence process is triggered by the identification of specific indicia—data points that indicate a potential U.S. or foreign tax residency. Systems must be configured to detect these indicators across all client data repositories reliably.

For FATCA, the system must identify U.S. connections. The key indicia include:

- U.S. citizenship or lawful permanent resident (green card) status.

- A U.S. birthplace.

- A U.S. residence or mailing address.

- A U.S. telephone number.

- Standing instructions to transfer funds to a U.S. account.

- A power of attorney granted to a person with a U.S. address.

For CRS, the scope is broader, covering tax residency in any participating jurisdiction. The primary indicator is a client's declaration of tax residency in a country other than where the institution is located. This requires a system capable of managing and validating tax identification numbers (TINs) and residency claims from over 100 different countries.

Due Diligence for New and Pre-existing Accounts

The required due diligence procedures differ based on whether an account is new or pre-existing. This distinction is critical for resource allocation and system design.

For new accounts, due diligence is performed at onboarding. The primary control is the self-certification form where the account holder declares their tax residencies. This document is a foundational piece of evidence. The process must ensure these forms are collected, validated for completeness and reasonableness, and stored in a verifiable manner.

For pre-existing accounts, financial institutions were required to conduct a retrospective review of their client base to identify reportable accounts. This typically involved an electronic search for indicia within existing data. For high-value accounts, the process was often more rigorous, sometimes including a manual review of paper records and consultation with the relationship manager.

A change of circumstance is a critical control point. An event like a client updating their phone number to a U.S. number or changing their residency address must automatically trigger a review of their FATCA and CRS status. This transforms compliance from a static check into a continuous monitoring function.

Key Differences Between FATCA and CRS Reporting

While sharing the goal of combating tax evasion, FATCA and CRS have operational differences that must be engineered into the compliance system. Failure to address these can result in significant compliance gaps.

The table below outlines the key distinctions for reporting operations.

| Aspect | FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act) | CRS (Common Reporting Standard) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | U.S. persons and entities. A unilateral regime where foreign institutions report to the U.S. IRS. | Tax residents of over 100 participating jurisdictions. A multilateral, reciprocal exchange of information. |

| Legal Basis | U.S. domestic law implemented through a network of bilateral Intergovernmental Agreements (IGAs). | An OECD standard implemented into the local law of each participating jurisdiction. |

| De Minimis Thresholds | Specific thresholds exist for pre-existing individual accounts ($50,000) and entity accounts ($250,000). | Generally, no de minimis thresholds for individual accounts. Pre-existing entity accounts below $250,000 are excluded. |

| Reportable Indicia | Focused exclusively on indicia of U.S. status (e.g., U.S. address, phone number). | Broader scope, primarily triggered by tax residency outside the institution's location. |

| Controlling Persons | Focuses on identifying "Substantial U.S. Owners" for Passive Non-Financial Foreign Entities (NFFEs). | Requires identification of "Controlling Persons" for Passive Non-Financial Entities (NFEs), based on AML/KYC rules. |

| Citizenship Test | U.S. citizenship is a primary indicator of U.S. person status, regardless of residency. | Citizenship is not a primary indicator. The focus is strictly on tax residency. |

Understanding these differences directly impacts the design of onboarding forms, the configuration of monitoring systems, and the structure of final reports.

Building a Defensible Classification System

The outcome of due diligence is a classification: is the account reportable or not? This decision must be recorded within core systems, linked to all supporting evidence.

An auditor must be able to select any account and trace a clear, logical path from the source client data and self-certification form to its final reporting classification. This requires a system that connects, not just stores, data. A client record should show the indicia identified, the self-certification received, any additional documentation provided to resolve ambiguities, and the final, timestamped classification made by an authorized user. This constitutes the foundation of an audit-ready fatca crs reporting framework, transforming a regulatory requirement into a verifiable operational control.

Data Collection and Reporting Mechanics

Once an account is classified as reportable, the focus shifts to data collection and submission. This is a technical process that demands precision. Successful fatca crs reporting depends on collecting the correct data elements, formatting them according to strict schemas, and maintaining a verifiable data lineage from source systems to the final report.

The objective is to produce a submission file that is both technically valid and factually accurate. A single error in a Tax Identification Number (TIN) or account balance can lead to rejection, regulatory inquiries, and a compliance failure. The entire process must be designed to ensure every data point in the final report is traceable to its origin.

Core Data Fields for Reporting

Both FATCA and CRS mandate a specific set of data for each reportable account. While local variations exist, the core requirements are consistent across jurisdictions. Systems must be configured to aggregate these fields accurately.

Tax authorities require the following information:

- Account Holder Information: Full name, address, tax residence jurisdiction(s), and TIN. For entities, the entity type is also required.

- Account Details: The account number or a functional equivalent.

- Financial Institution Information: The name and identifying number of the reporting institution.

- Account Balance or Value: The balance as of the end of the calendar year or other appropriate reporting period. If an account was closed during the year, that fact must be reported.

- Income Payments: The gross amount of interest, dividends, and other income credited to the account during the year.

This data is often distributed across multiple systems, such as a core banking platform, a CRM, and an investment management system. A primary operational challenge is aggregating this information without introducing errors. This requires robust data governance and regular reconciliation to maintain consistency.

This flow illustrates the systematic progression from account identification to data aggregation for the final report.

It is a structured path from indicia detection to the documented evidence that serves as the basis for reportable data.

Report Generation and Submission Schemas

Tax authorities do not accept data in arbitrary formats. Both FATCA and CRS reporting must adhere to specific XML (eXtensible Markup Language) schemas. The FATCA report is based on the IRS XML Schema v2.0, while CRS uses the OECD’s CRS XML Schema.

These schemas define the precise structure, data elements, and validation rules for the reporting file. The reporting system must be capable of transforming aggregated client and account data into a valid XML file that conforms to these technical specifications.

A compliant reporting system is more than just a data aggregator; it is a validation engine. The system must perform checks to ensure that TIN formats are correct for the specified jurisdiction, currency codes are valid, and all mandatory fields are populated before the file is generated. This preventative control minimises the risk of submission rejection.

The generated XML file is typically uploaded to the local tax authority via a secure government portal. The submission itself is a critical control point. Evidence of submission, including system-generated receipts and timestamps, must be retained as proof of timely filing. The absence of this evidence can create significant challenges during an audit, even if the report was accurate and submitted on schedule. A system that automatically captures and stores this proof is essential for demonstrating end-to-end compliance.

Managing Global Timelines and Jurisdictional Nuances

Effective fatca crs reporting requires not only data accuracy but also adherence to a complex calendar of jurisdictional deadlines. For a multinational financial institution, this presents a significant coordination challenge.

The reporting lifecycle begins well before the submission date, involving data cut-offs, aggregation and validation processes, and internal reviews. Each step is a control point designed to make compliance a predictable, managed process rather than a reactive, last-minute effort.

Navigating the Global Compliance Calendar

A primary operational challenge is the variation in FATCA and CRS reporting deadlines across jurisdictions. While many countries align their deadlines, sufficient differences exist to necessitate a dynamic, centrally managed global compliance calendar. This calendar serves as the single source of truth for coordinating activities across different teams and locations.

For example, Germany's Federal Central Tax Office (BZSt) typically sets its deadline for July 31. In contrast, India's reporting deadline can be as early as May. More details on these jurisdictional timelines are available through resources analyzing international reporting deadlines from pplaw.com.

Managing a global reporting schedule is fundamentally a project management discipline. The system of record should not only track deadlines but also assign ownership for each stage of the submission process, from data extraction to final confirmation. This creates a clear line of accountability for timeliness.

The Impact of Evolving Reporting Portals

Another source of operational complexity is the evolution of government reporting portals. Tax authorities periodically update or replace their submission systems to enhance security or functionality. These changes, while necessary, create operational risk if not managed proactively.

When a regulator announces a portal transition, such as the BZSt replacing its ELSTER portal, compliance and IT teams must collaborate closely. The transition requires:

- Technical Adaptation: Reconfiguring data exports and API connections to align with the new system's specifications.

- Process Redesign: Updating internal procedures and training personnel on the new submission workflow.

- Security Validation: Ensuring the new portal meets the organization's standards for transmitting sensitive data.

Failure to plan for these changes can result in missed deadlines or submission rejections, regardless of data quality. This necessitates continuous environmental scanning and proactive system maintenance, a principle we detail in our guide on how to build a NIS2 demonstrable control system.

Filing Nil Reports and Retaining Evidence

Even in the absence of reportable accounts for a given year, compliance obligations may not be complete. Many jurisdictions require the submission of a "nil report" to confirm that due diligence was performed and no reportable accounts were identified. This is a mandatory filing; failure to submit a required nil report is often treated with the same severity as a failure to report actual accounts.

Finally, retaining evidence of timely filing is a non-negotiable component of an audit-ready system. This evidence must include:

- The final XML file that was submitted.

- The official submission receipt or a confirmation screen capture.

- Internal system logs showing the submission timestamp and the user who performed the action.

This proof must be stored securely and be readily accessible. During an audit, demonstrating that you filed on time is as important as demonstrating what you filed. This systematic approach to evidence retention closes the loop on the reporting lifecycle, ensuring every action is documented and verifiable.

Building an Audit-Ready Compliance System

FATCA and CRS compliance should be the output of a system designed for traceability and verifiability, not the result of last-minute data aggregation and manual checklists.

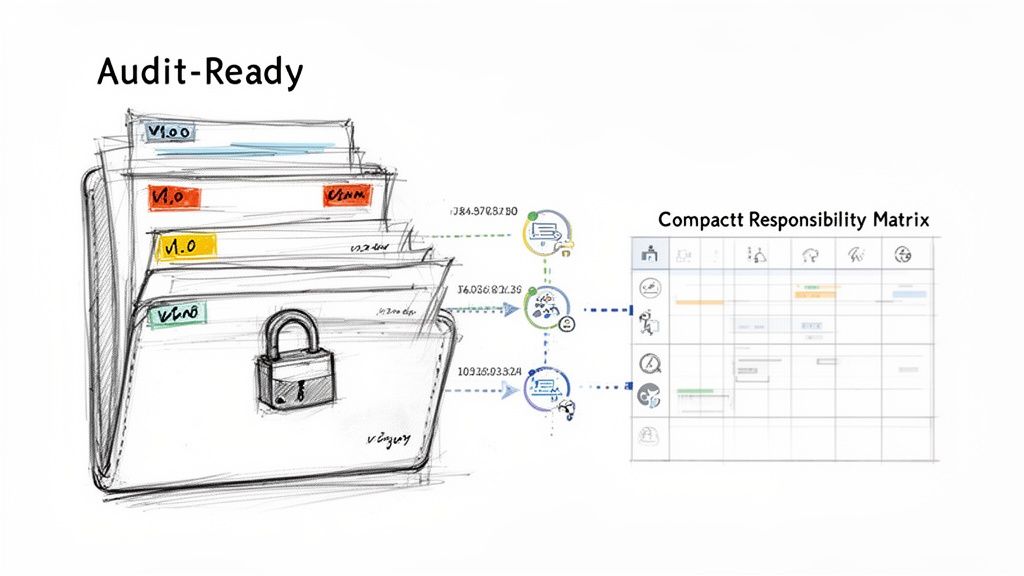

An audit-ready system transforms an audit from a disruptive inspection into a routine verification of operational integrity. The objective is to establish an unbroken chain of evidence from a regulatory requirement to an internal procedure, its governing control, and the proof that the control was executed. This treats compliance as a governance discipline built on systems, not just on documentation.

Establishing Clear Ownership and Responsibilities

A defensible system is built on accountability. The first step is to assign unambiguous ownership for every component of the FATCA and CRS process. A responsibility assignment matrix (RACI) is the appropriate tool for this.

This matrix maps specific compliance tasks to roles, clarifying who is Responsible for executing the work, who is Accountable for the outcome, who must be Consulted, and who needs to be Informed. For instance, a Relationship Manager may be responsible for obtaining a client's self-certification form, but the Head of Compliance is accountable for the integrity of the overall due diligence process. This distinction separates task execution from system ownership. An audit will test both.

A well-designed system makes accountability unavoidable. It logs which user performed an action, what evidence they reviewed, and when the decision was made. This immutable record is the most powerful tool for demonstrating that controls are not just designed but are operating effectively.

A Systematic Approach to Evidence Management

An audit-ready system is defined by its evidence. This evidence is a structured, version-controlled, and secure dataset that proves the compliance program is operating as designed. This requires moving beyond shared folders and spreadsheets to a purpose-built system.

Three pillars support effective evidence management:

-

Control Documentation Versioning: Policies and procedures evolve. A robust system versions these documents, linking each version to its period of applicability. This allows an auditor to assess the exact control that was in place during the review period.

-

Secure Data Encryption: FATCA and CRS data contains sensitive Personally Identifiable Information (PII). All evidence, from self-certifications to internal data files, must be encrypted both in transit and at rest. The use of strong standards like AES-256 is a baseline requirement.

-

Generating Secure Audit Packs: For an audit, evidence must be provided efficiently and securely. An audit pack should be a self-contained, indexed export of all relevant policies, procedures, control execution logs, and supporting evidence. The system should generate this pack as a secure, encrypted archive with a clear index for auditor navigation. Our article on the fundamentals of an ISO 9001 audit provides more context on preparing evidence for formal assessments.

This systematic approach to fatca crs reporting treats an audit as a verification of system design. When an auditor requests proof, the response is a predefined export, demonstrating control, preparedness, and a mature compliance posture.

Common Compliance Failures and How to Mitigate Them

Effective FATCA and CRS reporting systems are designed to prevent failures, not just detect them. Most compliance breakdowns are not sudden events but the result of latent weaknesses in due diligence, data management, or internal controls. Understanding these common failure points is the first step toward building a resilient system.

The most frequent source of error is incomplete or inaccurate due diligence. This stems from flawed client onboarding processes where self-certification forms are not properly collected or validated. A missing Tax Identification Number (TIN) or an unaddressed change of circumstance, such as a new foreign address, is sufficient to render a report incorrect and attract regulatory scrutiny.

Another critical failure point is poor data quality and integrity. When financial data is aggregated from multiple, unsynchronized systems, inconsistencies are inevitable. This leads to the reporting of incorrect account balances or income figures, undermining the integrity of the entire submission. Without robust data governance and reconciliation controls, the risk of filing inaccurate information is high.

Addressing Systemic Weaknesses

Mitigating these risks requires moving beyond manual checks and focusing on systemic controls. The objective is to design processes that make errors difficult to introduce.

This involves embedding automated checks and balances throughout the reporting lifecycle:

- Automated Indicia Searches: Systems should automatically scan client data for reportable indicia at onboarding and upon any subsequent update to client information.

- Mandatory Field Validation: Onboarding workflows must prevent account opening if a required self-certification form is incomplete or invalid.

- Data Reconciliation Controls: Automated scripts should run at defined intervals to compare data across source systems, flagging discrepancies for investigation.

A compliance failure is rarely a single point of error. It is typically a chain of small oversights—a missing document, an unverified data field, a lapsed control—that culminates in a non-compliant submission. Strengthening the system means reinforcing every link in that chain.

The consequences of systemic failure can be significant. For example, audits by India's Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) have revealed substantial compliance deviations in tax administration. One GST audit found 741 compliance deviations in 1,086 cases, while another identified 549 cases where taxpayer records were unavailable. The full findings on these compliance gaps from the CAG report-06943acb5ad7ae2.59486831.pdf) illustrate the scale of risk.

The only effective mitigation is to treat fatca crs reporting as a continuous process, not an annual project. You can learn more by reading our guide on implementing compliance as a continuous system. This approach ensures controls are always operating, data is consistently validated, and the system remains audit-ready by design.

The Future of International Tax Reporting

The domain of international tax transparency is not static. The introduction of frameworks like CRS 2.0 and the Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework (CARF) indicates that the scope of FATCA CRS reporting will continue to expand.

These new frameworks are not minor adjustments; they are designed to incorporate new asset classes and more granular data points into the automatic exchange of information. This represents a fundamental shift that requires financial institutions to re-evaluate their reporting architecture. The primary challenge, as always, is operational.

Adapting Systems for New Asset Classes

CARF, which specifically targets crypto-assets, requires firms to develop controls to identify, classify, and report transactions that may not involve traditional financial intermediaries. This is a significant engineering task, requiring the capture of new data types and their integration into existing compliance workflows.

Concurrently, CRS 2.0 is expected to broaden the definitions of financial assets and investment entities. This expansion will necessitate a comprehensive update of due diligence procedures and reporting logic to ensure these newly included assets and entities are identified and reported correctly.

The evolution from CRS to CRS 2.0 and CARF demonstrates a core principle: compliance is a continuous engineering discipline, not a one-time project. Systems must be designed for adaptability, allowing for the integration of new rules and data requirements without requiring a complete rebuild.

This evolution is global. India's adoption of the OECD's Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement (MCAA) on June 3, 2015, established the foundation for this level of transparency. Today, its over 4,000 Reporting Financial Institutions (RFIs) are preparing for CRS 2.0, highlighting the scale of work required to maintain compliant FATCA CRS reporting systems. The global impact of these reporting standards on neuronwealth.com provides additional context.

The trajectory of reporting is clear: more data, in greater detail, across more asset classes. Success depends on building robust, evidence-based systems capable of evolving in tandem with regulatory demands.