Governance, Risk, and Compliance (GRC) is a structured discipline for aligning an organisation's operational activities with its business objectives, while managing risk and meeting regulatory requirements. It is often misconstrued as a collection of separate, bureaucratic functions. In practice, GRC is an integrated system designed to ensure resilient, predictable operations, not merely to satisfy audit checklists.

The objective is to build a coherent framework that connects governance, risk management, and compliance into a single, functional system. This approach shifts the focus from reactive, audit-driven activities to proactive, systemic control.

GRC as an Engineering Discipline

Effective GRC implementation requires treating it as an engineering discipline, focused on designing, building, and verifying systems that perform reliably under operational pressure. This perspective moves an organisation from reacting to audits with checklists to proactively embedding operational controls into its core processes.

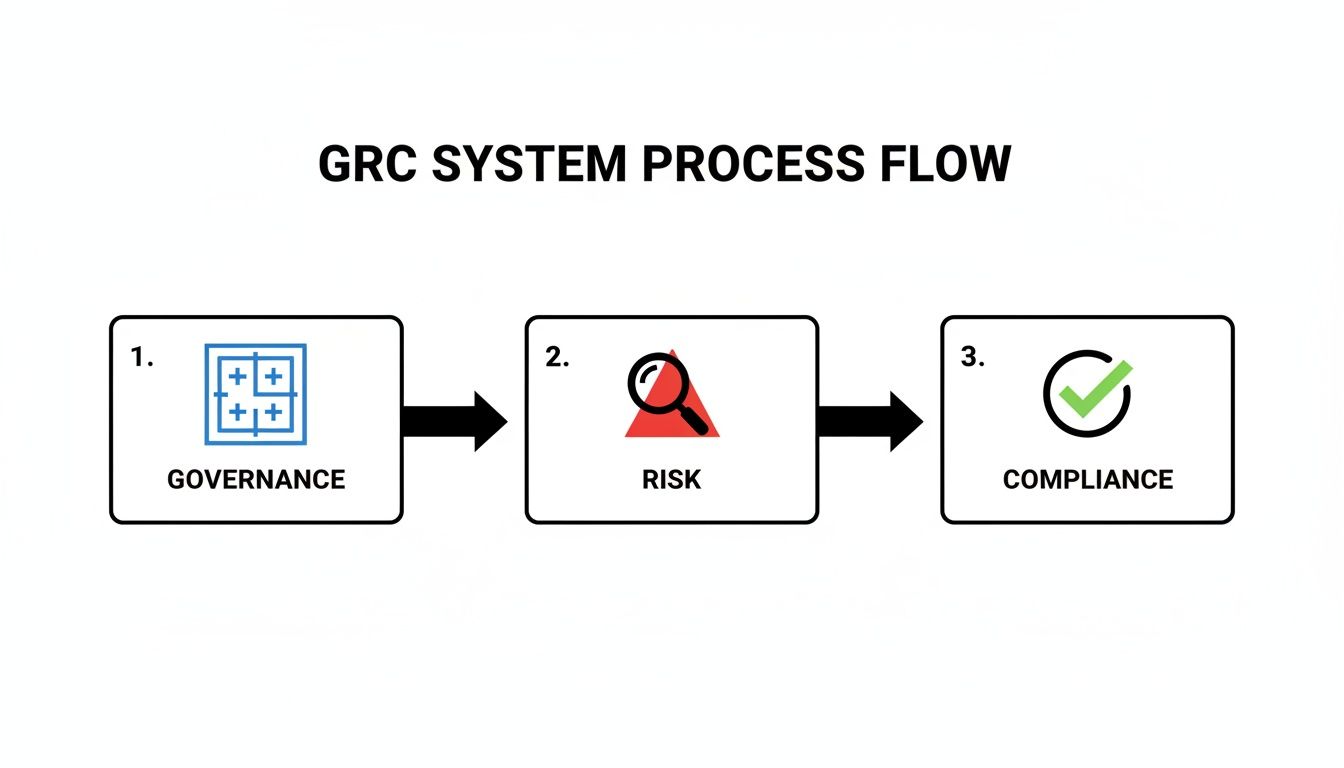

The three components of GRC are not separate organisational silos; they are interconnected functions within a single system designed to ensure the organisation operates as intended, particularly within regulated environments.

The Core Components of GRC

Each component serves a distinct purpose, but their value is realised only when they operate as a unified system.

-

Governance establishes the operational framework. It defines the policies, standards, and processes that guide decision-making and assigns accountability. It is the architectural blueprint for organisational control.

-

Risk Management is the diagnostic function. It is the continuous process of identifying, assessing, and mitigating threats that could prevent the organisation from achieving its objectives. It identifies potential points of failure and informs where controls are necessary.

-

Compliance is the verification function. It produces the auditable evidence demonstrating that the organisation adheres to both internal policies and external regulations. It closes the loop by verifying that controls designed under the governance framework are operating effectively.

A functional GRC framework connects these components into a continuous feedback loop. Governance sets the policies, risk management identifies threats to those policies, and compliance verifies that controls are mitigating those threats. Without this integration, an organisation is left with disconnected activities that are ineffective during a formal audit or a security incident.

This engineering-based approach is a requirement for modern regulations like DORA and NIS2. These frameworks mandate demonstrable resilience, which can only be achieved through systematic design, not last-minute compliance efforts. When GRC is treated as a core component of system architecture, it ceases to be a cost centre and becomes a foundation for operational stability and control.

The Mechanics of a Functioning GRC System

A Governance, Risk, and Compliance (GRC) programme is a practical system that translates high-level policies into specific, verifiable controls. Its effectiveness depends on the traceable relationship between policies, controls, evidence, and accountability. This chain of traceability is essential for both operational resilience and demonstrating compliance during an audit.

Policies are formal statements of intent, representing strategic decisions made by leadership. However, a policy is only a document until it is implemented through one or more testable controls. Controls are the specific mechanisms that enforce policies within the operational environment. Without this connection, a policy has no practical effect. A functioning GRC system makes this link explicit and, critically, auditable.

The process flow is logical: governance defines the policies, risk assessment identifies threats to those policies, and compliance activities provide the evidence that controls are managing those risks effectively.

This demonstrates that compliance is not an isolated function but the verifiable output of a structured GRC process.

From Policy to Action: Controls

Controls are the operational core of any GRC system. They are typically classified into three categories, and understanding their distinct functions is critical for designing a robust control framework.

-

Preventive Controls: These are designed to prevent an undesirable event from occurring. Examples include firewall rules that block unauthorised traffic or Identity and Access Management (IAM) policies that restrict permissions to critical systems. Their purpose is proactive defence.

-

Detective Controls: These are designed to identify and report that an undesirable event has occurred. Examples include log monitoring systems that alert on repeated failed login attempts or configuration management tools that detect unauthorised changes. They provide visibility and enable a timely response.

-

Corrective Controls: These are designed to remediate the impact of an incident after it has been detected. Examples include an automated process that isolates a compromised system from the network or a documented procedure for restoring data from backups.

A mature security architecture layers all three types of controls to create a defence-in-depth model. If a preventive control fails, a detective control should identify the failure, and a corrective control should mitigate the impact.

A high-level policy must be translated into specific controls, and each control must be designed to generate specific evidence of its operation.

Mapping Policies to Controls and Evidence

| Policy Statement | Technical Control | Required Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| "All access to production systems must be logged and reviewed." | Enable audit logging on all production servers and databases. | Server OS logs (e.g., syslog, Windows Event Logs); database audit logs; firewall logs showing access patterns. |

| "All access to production systems must be logged and reviewed." | Implement a Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) system to aggregate logs. | SIEM configuration file; dashboard screenshots showing log sources; alert rules for suspicious activity. |

| "All access to production systems must be logged and reviewed." | Conduct and document quarterly access reviews for all production system administrators. | Signed access review reports; screenshots from the identity management tool showing user roles; tickets documenting access removal. |

This table illustrates the direct line of traceability from intent ("log all access") to implementation (enabling logs) and finally to proof (the logs and review reports). This is the level of traceability required by auditors.

The Central Role of Evidence

The most critical output of any control is evidence.

Evidence is the verifiable, immutable proof that a control is not only designed correctly but is operating effectively over time. From an auditor's perspective, evidence is the primary basis for their assessment.

An auditor's role is not to trust policy documents but to verify operational evidence. Without clear, traceable evidence, a control cannot be considered effective from a compliance standpoint.

Evidence transforms a subjective claim ("our systems are secure") into an objective, demonstrable fact. This is why the entire lifecycle of evidence—its generation, collection, storage, and presentation—is fundamental. A well-designed system ensures every log, report, and configuration file can be traced directly back to the specific control it validates.

For a deeper exploration of this operational model, refer to our article on building compliance as a continuous system.

This complete traceability, from a high-level requirement to a specific log entry, is the non-negotiable foundation of a GRC system. It is what distinguishes a structured engineering discipline from a paperwork exercise and what ultimately makes an organisation resilient and auditable.

Navigating the Modern Regulatory Landscape

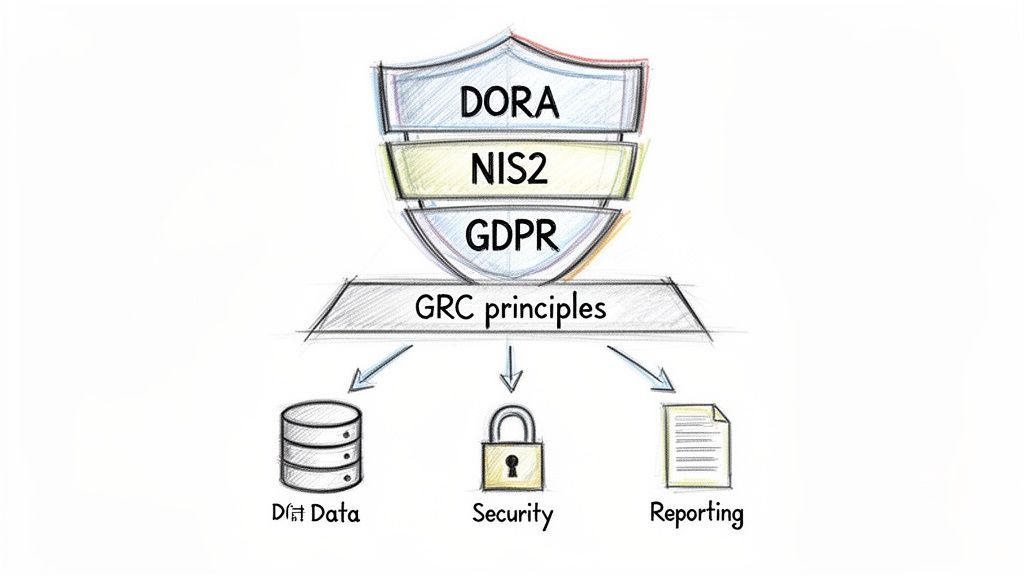

The current environment for governance, risk, and compliance is defined by a growing number of interconnected and often overlapping regulations. Frameworks such as the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), the NIS2 Directive, and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) have distinct objectives but are built upon common principles. By understanding these foundational principles, an organisation can design a single, efficient GRC system that satisfies multiple regulatory requirements.

Instead of focusing on the specific legal text of each regulation, it is more practical to focus on their operational demands. For example, DORA’s requirement for "demonstrable operational resilience" translates directly into specific engineering tasks: rigorous incident response testing, systematic third-party risk management, and the capability to produce evidence that these activities are performed consistently.

Similarly, NIS2’s focus on network security and GDPR’s mandate for personal data protection both necessitate clear governance structures, documented risk assessments, and robust controls that produce auditable evidence. While the specific controls may differ, the GRC principles required to verify their effectiveness are identical.

Identifying Common Principles

Treating each regulation as a separate project leads to duplicated effort and operational friction. A more effective strategy is to identify the common principles that underpin these regulations and build a unified GRC system to address them.

Most modern IT regulations are based on three universal requirements:

- System Security: The implementation and maintenance of technical and organisational measures to protect systems and networks.

- Data Protection: The assurance of confidentiality, integrity, and availability for sensitive data, particularly personal data.

- Transparent Reporting: The obligation to report security incidents, data breaches, and test results to regulatory authorities within specified deadlines.

These requirements form the foundation of a centralised governance, risk, and compliance programme. By designing controls that satisfy these core principles, an organisation can meet the demands of multiple frameworks simultaneously.

The Impact of Regulatory Complexity

This complexity has a measurable impact on organisations. The PwC Global Compliance Study indicates that nearly 90% of organisations report that increasing compliance complexity negatively affects their ability to manage IT systems. The data also shows that 44% of organisations are investing in compliance primarily to react to regulatory demands, while 42% are focused on keeping up with regulatory changes. Cybersecurity and data privacy are the top compliance priorities, each cited by 51% of organisations.

The objective is not to achieve compliance with DORA, NIS2, or GDPR as separate initiatives. The objective is to engineer a single, coherent operational system that is, by design, resilient and auditable. Meeting the requirements of various frameworks becomes a natural consequence of this system's design.

This approach shifts the focus from managing compliance checklists to engineering a fundamentally sound operation. A well-designed GRC system, grounded in robust enterprise risk management principles, provides a stable foundation. As new regulations emerge, the core processes do not need to be rebuilt. This is how an organisation transitions from a state of reactive compliance to one of continuous, verifiable control.

Common GRC Failures and How to Mitigate Them

Many GRC programmes fail in practice, not due to a single event, but from a fundamental misunderstanding of GRC as a continuous system rather than a series of discrete projects.

The Project Trap: Treating Compliance as a One-Time Event

A common failure is to treat compliance as a project with a defined start and end date, culminating in an audit. This approach misses the purpose of compliance, which is not a certificate but a continuous state of operational integrity.

This project-based mindset leads to the "audit scramble"—a period of intense, last-minute evidence gathering. This cycle is inefficient, stressful, and often leaves gaps for auditors to identify. A functional GRC system enables an organisation to be audit-ready by default, not just on the day of an audit.

Confusing a Tool with a System

Another frequent mistake is equating the procurement of a GRC tool with the implementation of a GRC system. A tool is an enabler; it cannot create a process where none exists or enforce accountability on its own. A system is the integrated framework of processes, controls, and responsibilities that a tool is designed to support.

Without clearly defined ownership and operational workflows, a GRC platform can become a repository of static data with little practical value. Accountability must be engineered into the process by assigning every control to a specific individual or team responsible for maintaining its operation and providing evidence.

The primary function of a GRC system is to create and enforce accountability. If a control cannot be traced to a named owner responsible for its evidence, the programme has a critical design flaw.

This lack of clear ownership is a common reason why the same audit findings recur. When no one is directly accountable for a control's performance, evidence collection is treated as a secondary task that is often neglected under operational pressure.

The Danger of Siloed Efforts

Finally, GRC fails when governance, risk, and compliance functions operate in isolation. When the security team manages technical controls without coordinating with compliance, or the risk team conducts assessments that do not inform governance policies, the result is a fragmented view of the organisation’s risk posture.

This disjointed approach creates operational blind spots and redundant effort. For instance, the IT team might resolve a security incident, but if the compliance team is not involved, the evidence required for regulatory reporting may not be collected properly. A unified operational view is necessary for effective decision-making.

The IT Risk and Compliance Benchmark Report highlights the real-world consequences. One study found that 47% of companies failed a formal audit two to five times in the last three years, indicating a systemic struggle with operational consistency. Another found that organisations managing risk reactively are significantly more likely to suffer a data breach.

Avoiding these failures requires treating governance risk and compliance as an engineering discipline. This demands systematic processes, unambiguous accountability, and a unified operational framework—not just disconnected tools and last-minute efforts.

Integrating AI and Technology into Your GRC System

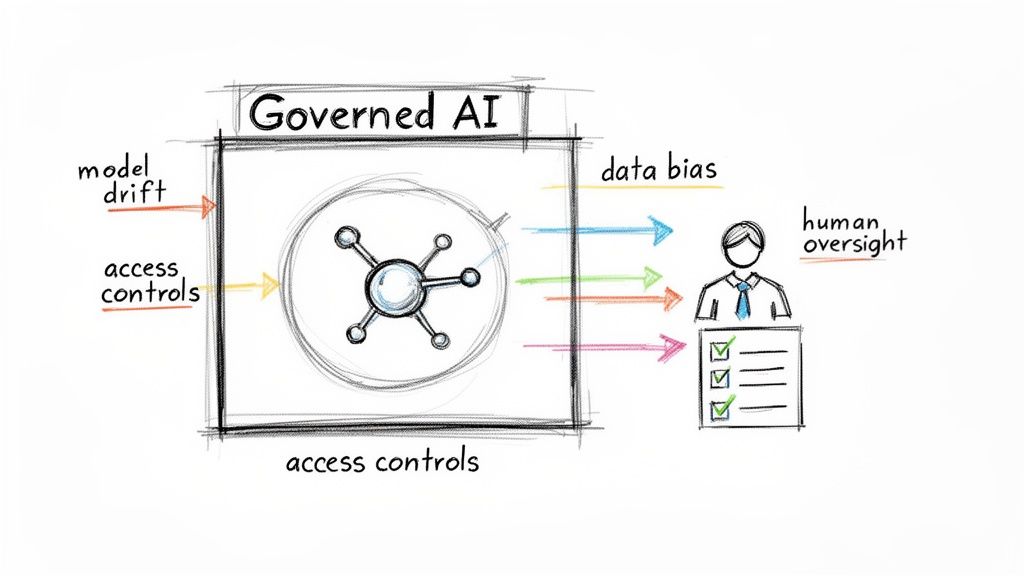

When introducing new technology, such as artificial intelligence, into a regulated environment, the existing GRC framework must be extended, not replaced. Technology is another component within the system. AI systems must be governed with the same discipline applied to any other critical infrastructure.

It is a common error to view AI as an autonomous agent. It is a system component that introduces new operational risks, and these risks require specific, well-designed controls to ensure stability and accountability. The core principles of GRC—clear governance, documented risk management, and verifiable compliance—must be systematically applied.

Governing New Technological Risks

The adoption of AI presents unique challenges that a mature GRC framework must address. In addition to traditional IT risks, AI introduces variables such as model drift, data bias, and opaque decision-making processes. These are not merely technical issues; they represent potential governance failures.

Specific controls must be designed to manage these risks:

- Model Drift: This occurs when an AI model's performance degrades as new data deviates from its original training data. Continuous monitoring is required to detect this. Evidence includes performance metric reports and recalibration logs.

- Data Bias: Rigorous data validation processes should be established before and during model training to identify and mitigate biases. Evidence includes data sourcing documentation, fairness metrics, and records of bias testing.

- Opaque Decision-Making: Require comprehensive documentation for all production models, detailing their architecture, data dependencies, and known limitations. For high-impact decisions, a human must be responsible for reviewing and approving AI-generated outputs.

Technology does not replace the need for governance; it amplifies it. The responsibility for a system's output always remains with a human, regardless of the level of automation. Accountability is non-negotiable.

The Governance Gap in Emerging Technology

The rapid adoption of new technologies often outpaces the development of mature governance frameworks, creating a significant risk gap. AI governance statistics show that while a majority of organisations use AI, only a small fraction have fully integrated AI governance into their operational frameworks. One common failure is a lack of sufficient access controls for AI systems, which has been identified as a contributing factor in many AI-related security breaches.

This governance gap represents a critical exposure. Integrating technology into a GRC system is an exercise in applying established principles. It requires clear documentation for AI models, strict access controls for development and production environments, and independent verification of outputs. Human oversight is not an optional add-on; it must be designed into the system from the beginning to ensure every component serves the organisation’s objectives without introducing unmanaged risk.

Building a Culture of Continuous Audit Readiness

The ultimate objective of a successful governance, risk, and compliance programme is to make the formal audit a non-event. It should be a periodic verification of a system that is already operating as designed on a continuous basis.

This requires a shift in organisational mindset from reactive, project-based audit preparation to a culture of continuous audit readiness. This state is not achieved by chance; it is the direct outcome of engineering a system where accountability, process, and evidence generation are integrated into daily operations. When controls are operating continuously and evidence is a natural byproduct of routine work, the stress and disruption of an impending audit are eliminated.

Establishing Systematic Accountability

Continuous readiness begins with absolute clarity of ownership. Every control must have a designated owner who is explicitly responsible for its operation and the evidence that proves it. A responsibility assignment matrix (RACI chart) is a simple and effective tool for establishing this.

This is not a bureaucratic exercise; it is a foundational practice that maps each control to a specific individual or team. It removes ambiguity and ensures that the people performing the work are also responsible for demonstrating its effectiveness. Without clear ownership, accountability gaps emerge, which invariably lead to evidence gaps during an audit.

An audit is not a test of a team's ability to locate documents under pressure. It is a verification of a system's ability to produce evidence of its normal, day-to-day operations. If evidence is difficult to produce, it indicates a flaw in the system itself.

Implementing Continuous Workflows

Once ownership is established, the next step is to build workflows for continuous evidence collection. This involves integrating evidence generation directly into existing operational processes, rather than treating it as a separate, manual task.

For example, a change management ticket should be configured to automatically capture all necessary approvals and deployment logs. When designed this way, the ticket itself becomes a complete evidence package for that change, without requiring additional manual effort.

This workflow-driven approach ensures that evidence is collected in real-time, contextually linked to the operational activity, and consistently formatted. By automating this process, an organisation builds a reliable and traceable audit trail over time, not just at a single point. You can learn more about this in our guide to collecting and managing audit evidence.

The right tools are important for this. An operational platform should provide clarity, traceability, and an efficient means of managing evidence. It supports the system by making it straightforward for control owners to submit proof and for managers to verify its completeness.

Ultimately, building a culture of continuous readiness transforms GRC from a periodic, costly exercise into a strategic asset. It demonstrates that an organisation's governance is not just a set of policies but a living, operational reality that contributes to a more predictable and resilient business.

Frequently Asked Questions About GRC

Here are practical answers to common questions about implementing a Governance, Risk, and Compliance system. The focus is on operational clarity, not academic theory.

What is the difference between GRC and Integrated Risk Management?

The terms are often used interchangeably, but they refer to different concepts.

GRC is an operational discipline. It is the framework for implementing policies, managing specific risks, and collecting evidence to demonstrate compliance.

Integrated Risk Management (IRM) is a broader, strategic concept. It aims to provide leadership with a comprehensive and aggregated view of risk from all parts of the business—including IT, finance, and operations—to inform strategic decision-making.

In essence, a functional GRC programme is a critical component of an IRM strategy, but it is not the entirety of it.

We are a small organisation. Where should we begin with GRC?

For smaller or less mature organisations, the most effective starting point is with the fundamentals of governance. Do not begin with complex risk registers or GRC tools.

Start by documenting clear, simple policies for critical operational areas, such as access control, change management, and data handling.

Next, assign an owner to every policy. Use a simple matrix to map accountability for each policy to a specific individual. This basic structure of documented rules and clear ownership provides the necessary foundation for subsequent risk assessments and compliance activities.

The initial goal is to build a system of accountability. A clear policy with a designated owner is more valuable than a sophisticated risk register that is not acted upon. Without clear governance, risk and compliance efforts lack direction and authority.

How do you measure the success of a GRC programme?

The success of a GRC programme is not measured by a compliance score or a certification. It is measured by its impact on operations.

A successful programme results in a state of continuous audit readiness, where an external audit becomes a routine verification rather than a disruptive event.

Indicators of a successful programme include:

- A reduction in repeat audit findings over time.

- The ability to produce evidence for any control on demand, without a last-minute effort.

- Audit cycles that are faster, more predictable, and consume fewer internal resources.

- A clear, traceable line from a regulatory requirement down to a specific piece of operational evidence.

Ultimately, a mature governance, risk, and compliance system makes the organisation more predictable and resilient, which is its primary business value.

Building a system for continuous audit readiness requires a toolkit designed for clarity, execution, and traceability. AuditReady provides an operational platform to manage policies, controls, and evidence, helping you move from reactive scrambles to a state of verifiable control. Streamline your preparation for frameworks like DORA and NIS2. Learn more and sign up.