A business impact analysis (BIA) isn’t just another report. It’s a systematic way to determine what happens when your critical business functions go offline. It quantifies both financial and non-financial damage over time, providing the evidence needed to build recovery strategies that are aligned with real operational needs.

Thinking of Business Impact Analysis as a System

The biggest mistake is treating a BIA as a static document. It’s not. A BIA should be a dynamic system for understanding how your organization really operates. Its goal is to map out the potential fallout from a disruption, framing it as an engineering and governance challenge rather than a compliance checkbox. This approach reveals the often-hidden connections between processes, technology, and people.

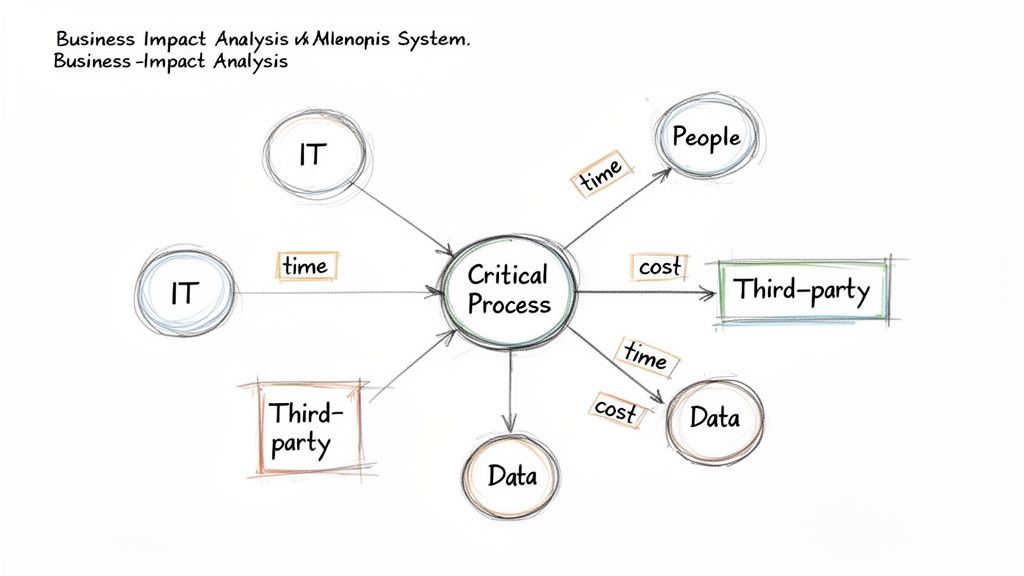

The core idea is simple: every part of your organization depends on other parts to function. A BIA provides the objective evidence to identify which functions are mission-critical based on the real-world impact if they fail.

The Purpose of a BIA

At its heart, a BIA connects a specific business process to its potential impact. It answers one fundamental question: “What are the consequences if this process goes down for an hour, a day, or a week?” The answer provides a solid foundation for every decision and resource you allocate to resilience.

A well-run BIA delivers clear outcomes:

- Identification of Critical Processes: Pinpoints the functions essential for your organization’s survival.

- Dependency Mapping: Documents the IT systems, people, third-party vendors, and data each process requires.

- Quantification of Impacts: Measures potential damage across categories such as financial loss, regulatory fines, and brand impact.

You cannot protect what you do not understand. By systematically mapping dependencies and quantifying potential losses, a BIA provides the data required to build a resilient operational framework.

BIA as a Governance Tool

Viewed as a system, the BIA transforms from a one-off assessment into a governance tool. Its findings become verifiable evidence to justify investments in backup systems, alternate suppliers, or staff. This systematic approach is a vital part of any real enterprise risk management framework.

Rather than assumptions, a rigorous BIA provides a traceable, defensible rationale for strategic choices. The documented results become the blueprint for business continuity and incident response plans that are focused on your organization’s most critical needs.

Setting the Scope and Objectives for Your BIA

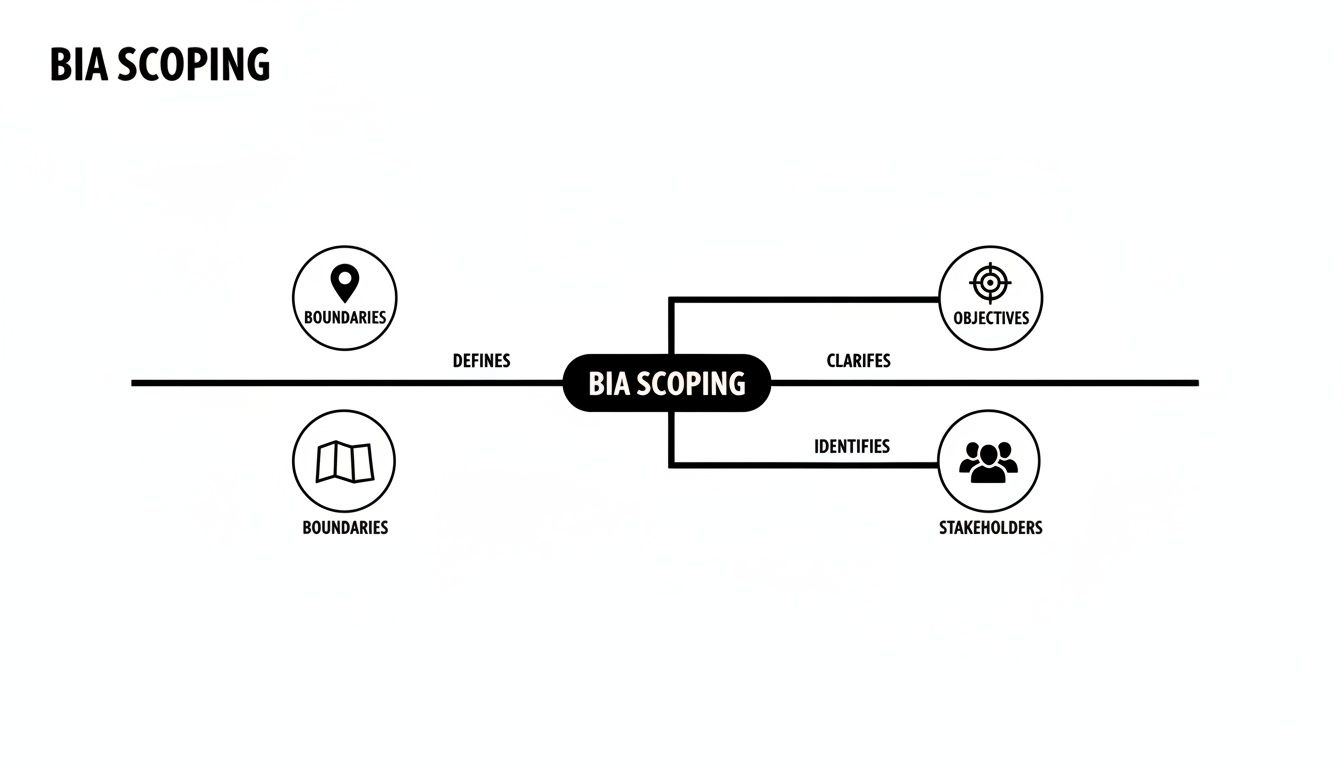

A Business Impact Analysis fails when it tries to analyse every process at once. Without a clear scope, the process becomes unmanageable and delivers little value. The first step is to define what matters most.

You can scope the BIA to a department, a critical service, or a technology that powers a core function. The goal is to choose a segment that is important enough to analyse and small enough to be examined thoroughly.

For example, a financial firm might focus on its retail banking payment processing systems because their failure has immediate and severe consequences.

What Are We Trying to Achieve?

Once you have your scope, define specific, measurable objectives. Clear goals drive a focused investigation; vague objectives produce ambiguous results.

Typical BIA objectives answer:

- What breaks first? Identifying processes that can’t be offline for more than a few hours.

- What do we fix first? Prioritizing restoration of business functions and systems.

- How fast do we need to fix it? Calculating Recovery Time Objectives (RTOs) and Recovery Point Objectives (RPOs) for critical processes.

An effective BIA is a targeted assessment designed to answer specific questions about operational resilience, linking directly to broader continuity and risk goals.

Getting Everyone on the Same Page

A BIA cannot be a side project for IT or risk. Its credibility depends on buy-in from business leaders, compliance officers, and IT managers. Business leaders define what “critical” means in terms of money and reputation. Compliance officers ensure regulatory scrutiny is addressed. IT managers verify system dependencies.

This alignment is the foundation of the entire process. When everyone agrees on scope and objectives before work starts, data is accurate, recommendations are practical, and the exercise delivers real value.

Identifying Critical Processes and Quantifying Their Impact

A BIA begins with discovery: mapping what your business actually does and what it relies on. This isn’t a list of every asset, but a focused investigation into the components whose failure causes the most damage.

For instance, a customer support team may depend on a CRM, phone platform, and knowledge base. The BIA traces these connections to show how the loss of one component halts the entire process.

Broadening the Definition of Impact

Focusing only on direct financial loss misses much of the picture. A BIA must measure the full spectrum of potential damage, both quantitative and qualitative.

- Financial Impact: Lost revenue, SLA penalties, and recovery overtime. Unplanned downtime can exceed $300,000 per hour for mid-to-large enterprises, with costs reaching significant levels per minute.

- Regulatory and Compliance Impact: Fines, sanctions, or breach notifications under regulations like DORA, NIS2, or GDPR.

- Reputational Impact: Erosion of customer trust, negative headlines, and brand damage that outlasts the immediate incident.

- Operational Impact: Breakdown of processes, lost productivity, and persistent inefficiencies after recovery.

- Contractual Impact: SLA penalty payments and loss of key customers due to contract breaches.

This diagram shows the inputs for scoping a BIA—defining boundaries, clarifying goals, and identifying stakeholders.

Impact Categories and Measurement Metrics

| Impact Category | Description | Quantitative Metric Example | Qualitative Metric Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial | Direct monetary losses and costs. | Revenue lost per hour of downtime. | Shareholder confidence drop. |

| Regulatory | Fines, penalties, and sanctions. | € value of GDPR fine based on revenue. | Mandatory public breach notification. |

| Reputational | Damage to brand, trust, and public image. | Cost of a PR campaign to restore trust. | Negative sentiment score on social media. |

| Operational | Disruption to internal processes and productivity. | Number of unprocessed orders per day. | Low employee morale and productivity. |

| Contractual | Failure to meet Service Level Agreements (SLAs). | SLA penalty payments to customers. | Loss of a key customer due to breach. |

This categorization ensures no critical angle is missed when assessing disruption costs.

A Methodology for Gathering Defensible Evidence

A credible, auditable BIA relies on evidence, not assumptions. Use structured interviews and workshops with subject matter experts, focusing on workflows, dependencies, and time-based impacts. Every assessment must be supported by data—historical sales figures, contractual clauses, or system logs.

A defensible BIA separates subjective opinion from objective fact. Every impact assessment must be traceable to documented evidence.

Consistent documentation in a controlled format creates a reliable audit trail. A document management system can support this process, ensuring all evidence is traceable and controlled.

Defining RTO and RPO to Build System Resilience

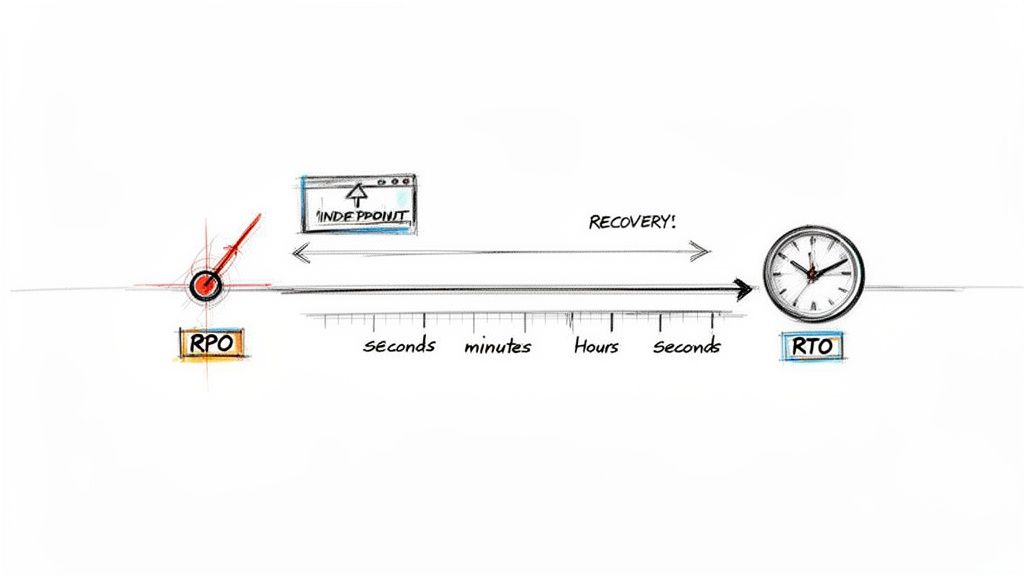

Once impacts and dependencies are clear, you derive two critical metrics: Recovery Time Objective (RTO) and Recovery Point Objective (RPO).

These metrics answer two fundamental questions: “How fast must we recover?” and “How much data can we afford to lose?” The answers drive system architecture, backup schedules, and third-party agreements.

Differentiating RTO and RPO

- Recovery Time Objective (RTO): The maximum time a process can be down before consequences become unacceptable. It defines how quickly you must restore operations.

- Recovery Point Objective (RPO): The maximum acceptable amount of data loss, looking backward from disruption. It defines backup or replication frequency.

Meeting both objectives is essential: you can restore quickly but lose critical data, or preserve all data but take too long to restore systems.

RTO governs recovery time, RPO governs data loss. A successful plan meets both.

Deriving Metrics from Impact Analysis

RTO and RPO emerge from the BIA’s evidence of operational, financial, and regulatory impacts. For a high-transaction e-commerce platform, the BIA may show:

- RTO of 15 minutes due to high revenue loss.

- RPO of less than one minute to prevent data inconsistency.

In contrast, an internal HR reporting system might have:

- RTO of 48 hours, as a brief outage is manageable.

- RPO of 24 hours, with daily backups sufficing for historical data.

Documenting and Justifying RTO and RPO

Every RTO and RPO must be documented with:

- Approved values.

- Impact metrics that justify them.

- Stakeholder sign-off (process and system owners).

This traceability turns technical targets into formal business requirements, ensuring resilience investments align with critical needs.

Integrating BIA Outputs with Governance and Compliance

A BIA performed in isolation produces only a report. When it feeds into governance, risk, and compliance (GRC) systems, it drives a defensible operational resilience programme.

Mapping BIA to Regulatory Requirements

Regulations like DORA, NIS2, and GDPR require a systematic, risk-based approach. A BIA identifies “critical and important functions” (CIFs), linking operational reality to specific controls.

- DORA and NIS2: Classify functions based on customer and market impact.

- Incident Response: Use RTOs to define official response timelines.

- Business Continuity Plans: Scope and priorities align with BIA findings (e.g., 24-hour vs. 15-minute RTOs).

Traceability is key. An auditor should link any control back to a BIA finding.

Creating an Audit-Ready Evidence Trail

A BIA is a governance component whose outputs serve as audit evidence. To satisfy audit requirements:

- Clear Ownership: Assign owners for each process and metric.

- Version Control: Maintain a history of updates.

- Secure Documentation: Store findings in a controlled environment.

This approach proves decisions are based on methodical analysis, not guesswork.

Common BIA Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even a well-designed BIA can falter in execution. Awareness of common errors ensures your BIA delivers real, lasting value.

Avoid Over-Ambitious Scope

Attempting to analyse every business process at once leads to superficial results. Instead, start with a few critical services whose failure would cause severe damage. This delivers faster value, refines your methodology, and builds support for subsequent phases.

Enforce an Evidence-First Mindset

A credible BIA requires traceable data. Insist that every impact claim—such as an RTO of one hour—is backed by financial reports, SLA terms, or system logs. This turns the BIA into a rigorous, audit-ready assessment rather than a subjective survey.

Treat the BIA as a Continuous System

Your organization changes over time. A BIA must be reviewed and updated at least annually, and whenever significant events occur:

- New product or service launch.

- Major technology migration.

- Introduction of new regulations.

- Key supplier changes.

This keeps your recovery plans aligned with current operations.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Difference Between a BIA and a Risk Assessment?

A Business Impact Analysis focuses on the consequence of a disruption—“How bad is the damage?”

A Risk Assessment focuses on the cause—“What could go wrong, and how likely is it?”

The BIA’s outputs (RTO, RPO) inform the risk assessment by highlighting what matters most.

How Often Should a Business Impact Analysis Be Conducted?

A BIA is a living document. Conduct a formal review at least annually and update it after significant changes, such as product launches, tech migrations, new regulations, or organizational restructures.

Who Should Be Involved in a Business Impact Analysis?

A BIA requires a cross-functional team:

- Business Process Owners for operational insight.

- IT Managers and System Owners for technical dependencies.

- Finance Representatives for financial impact metrics.

- Compliance and Legal Officers for regulatory considerations.

- Senior Leadership for ultimate buy-in and accountability.

A BIA is the foundation for understanding operational risk and building genuine resilience. For guidance on integrating BIA into a continuous compliance approach, see Learn more about building a continuous compliance system.