ESG due diligence is not a corporate responsibility exercise. In regulated IT, it is a systematic evaluation of environmental, social, and governance risks embedded within operational systems and supply chains. It is an integral component of core risk management, particularly where frameworks like DORA and NIS2 impose requirements for resilience and third-party oversight. The process centers on evidence, traceability, and accountability.

Defining the Scope of ESG Due Diligence

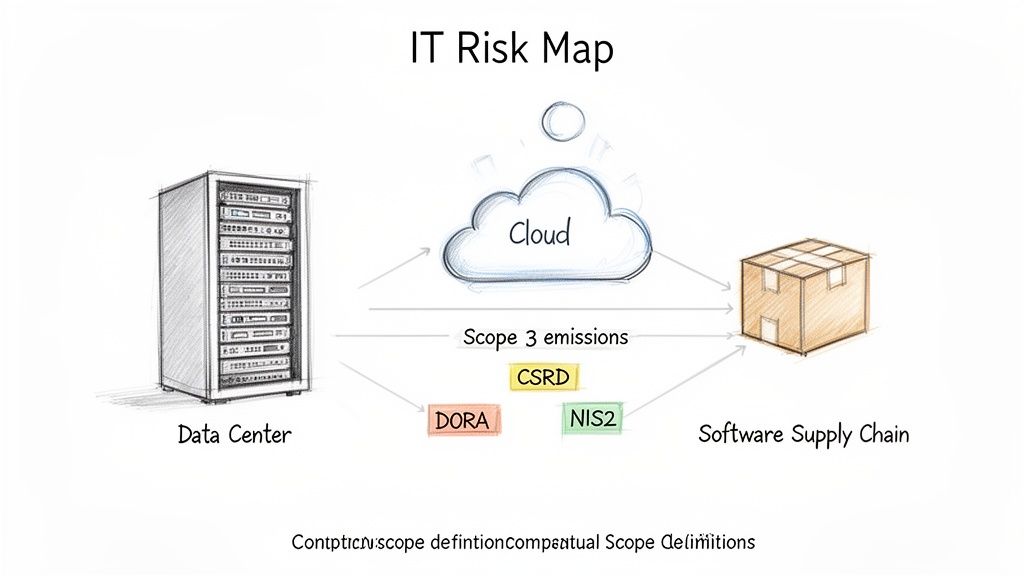

The effectiveness of an ESG due diligence process depends on a clearly defined and justifiable scope. For CISOs and compliance professionals, this requires translating broad ESG principles into specific, measurable IT risks. Generic templates are insufficient. The scope must address the operational realities of data centers, cloud infrastructure, and the software supply chain.

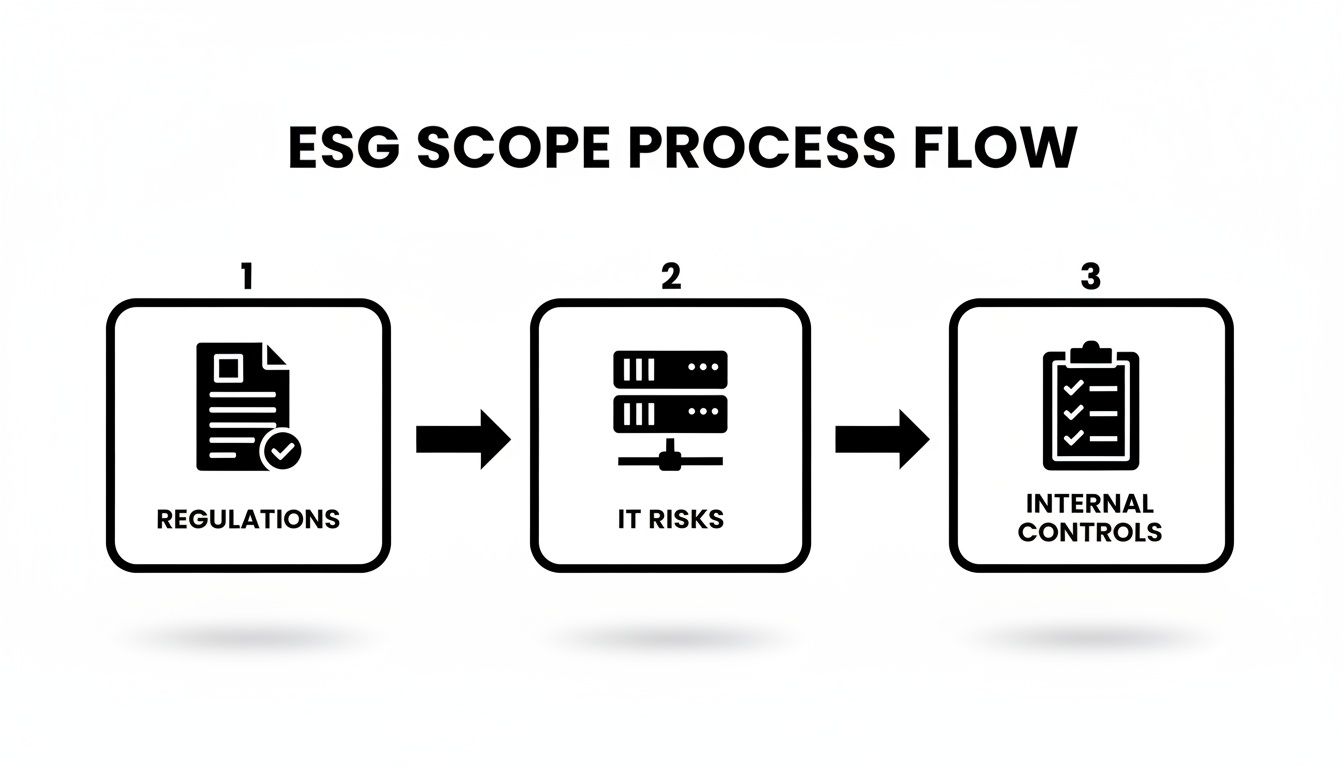

The process begins by identifying material risks unique to an organization's technology stack and regulatory obligations. A systematic method is required to map external mandates to internal systems and controls.

From Regulatory Mandates to IT Risks

The requirement for structured ESG due diligence in the European IT sector is increasingly driven by directives like the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). This regulation mandates comprehensive ESG disclosures for approximately 49,000 organisations beginning in 2025-2026.

This has immediate consequences for technology-dependent firms. Data centers and cloud services are significant energy consumers, responsible for up to 2-3% of global electricity consumption and are a primary source of Scope 3 emissions.

A functional scope must therefore address specific, regulation-grounded questions:

- Environmental: What is the carbon footprint of our primary cloud provider? What are the verified Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) metrics for our on-premises data centers?

- Social: What are the labor practices of our hardware suppliers? How do we verify our software dependencies do not originate from sanctioned entities?

- Governance: How do we ensure our AI models are developed and deployed without introducing unacceptable bias? What are the board-level oversight mechanisms for our ESG policies?

A well-defined scope converts these high-level questions into auditable criteria. For further detail on structuring this, our guide on building a cyber risk strategy and governance framework provides a relevant model.

This process flow illustrates how regulatory drivers inform IT risks, which in turn dictate necessary internal controls.

The path is direct: compliance obligations inform practical risk management. ESG is not an isolated function; it is a core component of operational governance.

Establishing Materiality and Boundaries

Not all ESG factors carry equal weight. Materiality is the principle of focusing on issues that have a significant impact on the organization’s operational and financial performance, as well as its external environment.

A common process failure is an overly broad scope that attempts to address every possible ESG issue. A defensible process focuses on a limited set of material risks that are deeply evidenced, rather than a wide set of risks that are superficially addressed.

To set clear boundaries, several concrete actions are necessary:

- Identify High-Impact Systems: Pinpoint the most critical IT assets, such as primary cloud environments, key software suppliers, and physical data infrastructure.

- Map Regulatory Overlap: Analyze where directives like DORA, NIS2, and GDPR intersect with ESG concerns. For example, DORA's third-party risk management requirements align directly with supply chain due diligence under the 'Social' and 'Governance' pillars of ESG.

- Define Risk Criteria: Establish clear, unambiguous criteria for what constitutes an acceptable or unacceptable risk, such as a maximum PUE for data centers or a requirement that suppliers hold specific labor certifications.

The following table outlines this in practical terms.

Key Focus Areas for IT-Specific ESG Due Diligence

| ESG Domain | IT-Specific Focus Area | Regulatory Driver Example |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Data center energy efficiency (PUE), cloud provider carbon footprint, hardware lifecycle management, e-waste policies. | CSRD requirements for Scope 3 emissions reporting. |

| Social | Supply chain labor practices (hardware & software), ethical AI development, employee data privacy. | Supply Chain Act (LkSG) for vendor due diligence; AI Act for ethical algorithm deployment. |

| Governance | Board-level oversight of ESG risks, transparency in AI decision-making, data ethics policies, third-party risk management. | DORA requirements for ICT third-party risk management; NIS2 focus on management accountability. |

This table illustrates the connection between high-level ESG domains and concrete IT operations driven by specific regulations.

By defining a precise scope, an organization builds an audit-ready foundation. This ensures efforts are focused, efficient, and directly linked to the core risks and compliance mandates the organization faces, treating ESG as a discipline of engineering and governance.

Mapping Controls to Policies and Ownership

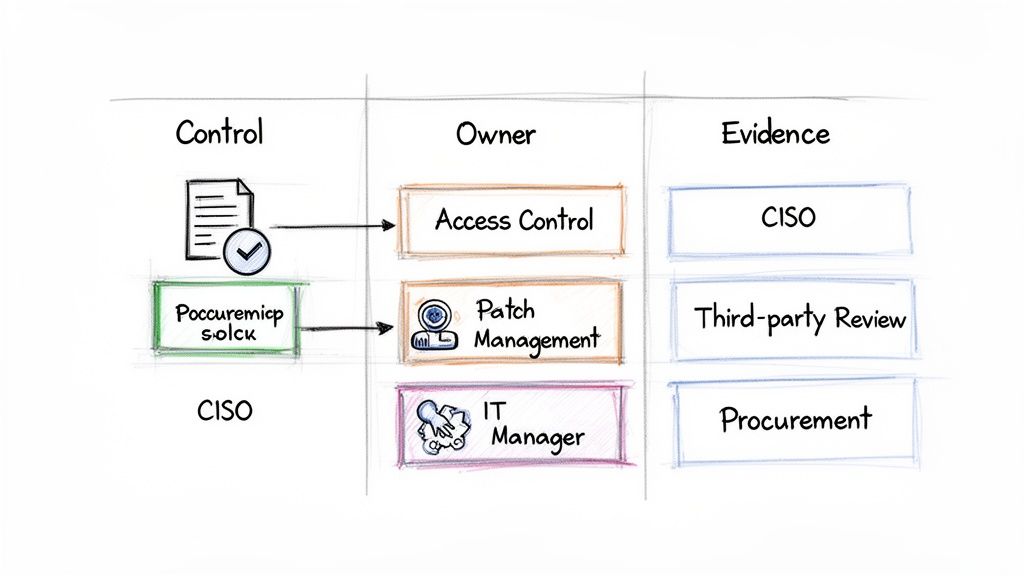

A well-defined scope prevents wasted effort. Its utility is realized only when high-level policies are translated into tangible, operational controls. This is where the theory of ESG due diligence intersects with the practice of system governance.

The objective is to create an unbroken line of accountability from a policy statement to the individual responsible for its implementation. This process requires a critical distinction between proactive systems and reactive checks. Controls are the mechanisms that ensure compliance by design, such as a configured access policy or an automated energy report. Audits serve to verify that those controls are operating effectively.

An audit cannot create compliance; it can only measure it.

Building the Ownership Matrix

To eliminate ambiguity, an Ownership Matrix is necessary. This is not a task list but a core governance document that maps every control to a specific role within the organization. It answers a single question: who is accountable for this control and for providing evidence of its effectiveness?

The matrix enforces clarity and addresses the common problem of "assumed responsibility," where critical controls are neglected because no owner was formally assigned. This is a classic failure point in audits.

For example, an ESG policy might state, "We commit to minimizing the environmental impact of our data centers." This is a sentiment, not an auditable control. It must be broken down:

- Control E-DC-01: "Monthly Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) reports must be generated for all on-premise data centers." This is specific and measurable.

- Owner: The IT Manager. This individual is accountable for the monitoring system and the reports.

- Evidence: The monthly PUE reports, stored in a secure, versioned repository.

This clear line from policy to control to owner is unambiguous proof of governance. For a deeper examination of this structure, our article on governance, risk, and compliance offers more context.

Documenting Mappings for Audit Scrutiny

The mapping itself must be documented to withstand an audit. Regulators, particularly under frameworks like DORA, are trained to identify gaps in accountability. This documentation is the first line of defense.

Traceability is paramount. An auditor must be able to select any ESG policy statement and follow the documentation directly to the control, its owner, and the supporting evidence. This creates a self-contained system of proof. The goal is to present a system so well-documented that the audit becomes a verification of a working process, not a forensic investigation.

A Practical Example of Mapping

Consider another example for the "Social" pillar:

- Policy Statement: "We ensure our software supply chain is free from components sourced from sanctioned entities."

- Control S-SC-01: "All third-party software libraries must be scanned against a maintained list of sanctioned entities before production deployment."

- Owner: The CISO is accountable for the scanning process and the associated tools.

- Evidence: Scan reports from each production release, including timestamps and signatures.

This detailed mapping provides auditors with a clear path. It demonstrates that ESG is not merely a policy document but an integrated part of operational risk management, showing mature governance where responsibility is assigned, not assumed.

Building a System for Evidence Collection

Collecting evidence for ESG due diligence is not an administrative task; it is an engineering discipline. Simply gathering documents is insufficient. A system must be built to guarantee the integrity, traceability, and security of the proof behind ESG claims. This system connects controls to auditor verification and forms the operational backbone of the program.

What Constitutes Verifiable Evidence

The required evidence is diverse, spanning all three ESG pillars. For an IT organization, this translates into specific, tangible artifacts.

- Environmental Controls: This includes data center Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) reports, utility bills proving renewable energy sources, or waste disposal certificates for retired hardware.

- Social Controls: Evidence may include supplier labor audit reports, anonymized employee training records on data ethics, or results from internal phishing simulations that demonstrate security awareness.

- Governance Controls: This covers board meeting minutes where ESG risks were discussed, signed policy documents with full version histories, or access control logs for critical systems.

Each piece of evidence must be managed with precision, requiring an engineering mindset.

Ensuring Evidence Integrity and Security

The credibility of the entire ESG process rests on the integrity of its evidence. If an auditor cannot trust a document's authenticity, the control it supports is effectively unverified. Robust technical safeguards are not optional; they are a core requirement.

An auditor should be able to assume that any evidence presented from the system is authentic, unaltered, and was accessed only by authorized personnel. The system’s design is as important as the evidence it contains.

The objective is to protect sensitive data while making it available for verification. This demands a multi-layered approach.

Key System Components for Evidence Management

A purpose-built system for evidence management must include several non-negotiable security components.

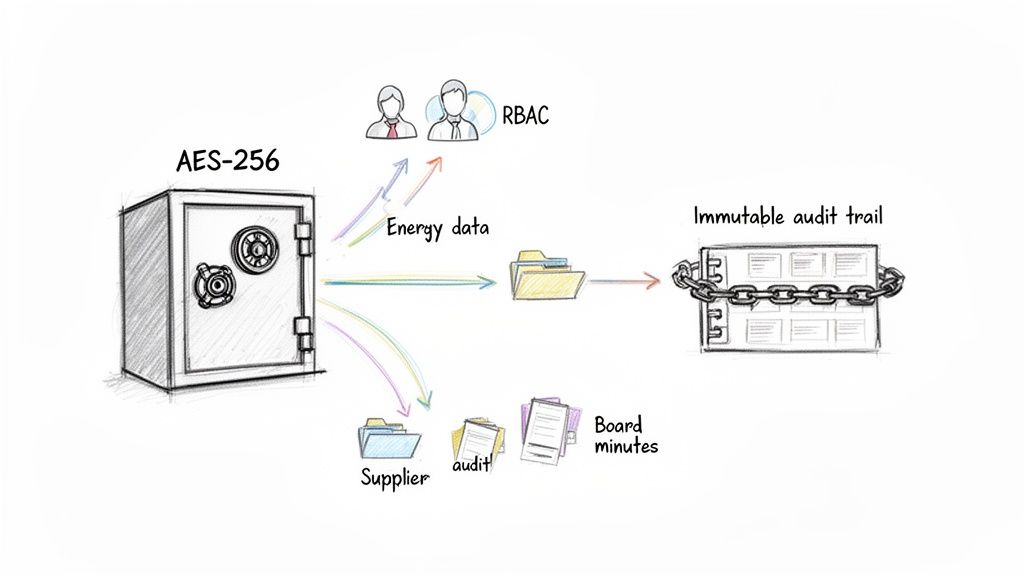

-

Encryption at Rest: All stored evidence must be encrypted using strong, industry-standard algorithms like AES-256. This is a baseline control that ensures data remains unreadable even if the underlying storage is compromised.

-

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC): Access to evidence must be restricted based on role. An IT manager might upload PUE reports, while only a compliance officer can access supplier audit findings. This enforces the principle of least privilege.

-

Immutable Audit Trails: Every action—upload, view, download, modification—must be recorded in an append-only log. This creates an unchangeable history, proving who did what and when. For an auditor, this trail is crucial for verifying the chain of custody and ensuring evidence has not been tampered with.

These technical controls create a secure, verifiable repository. Our detailed guide on audit evidence explores how these concepts contribute to a state of continuous compliance.

Addressing Practical Challenges in Evidence Management

Beyond security, operational friction can undermine the process. Two common points of failure are version control and audit readiness. An auditor requires the specific version of a policy that was in effect during the audit period, not the most recent one. A proper system maintains a complete version history, allowing for the retrieval of point-in-time evidence.

Finally, the format of the evidence is important. Preparing it in an audit-ready format means it is organized, indexed, and easily traced back to the specific control it supports. This transforms an audit from a search for documents into a systematic review, demonstrating foresight and mature governance.

Assessing Third-Party and Supply Chain Risks

An organization’s ESG risk profile extends deep into its supply chain, where the most significant environmental, social, and governance vulnerabilities often reside. Effective ESG due diligence demands a systematic, evidence-based process for assessing vendors, partners, and suppliers.

This is a core component of operational resilience, directly supporting mandates in frameworks like NIS2 that require a clear understanding of supply chain dependencies. The goal is to verify claims, not merely collect them.

Designing Assessments That Uncover Risk

A strong third-party assessment is built on a questionnaire that demands proof, not promises. It must be designed to compel suppliers to support their ESG claims with verifiable evidence, making it more difficult to obscure poor practices. Simple yes/no questions are insufficient. Queries must elicit detailed responses and documentation.

- Ineffective question: "Do you have an environmental policy?"

- Effective question: "Provide a copy of your environmental policy, including its last review date and the name of the accountable owner. Also, supply the energy consumption data for the last 12 months for the specific facility that services our account."

This approach forces a supplier to produce tangible artifacts. The absence of evidence is as informative as the evidence itself. The questionnaire becomes a diagnostic tool rather than a formality.

A Secure Process for Requesting and Verifying Evidence

Exchanging sensitive information with third parties introduces both security and logistical challenges. A secure, auditable method is required to request, receive, and store supplier evidence. A purpose-built system can facilitate this by providing a secure, one-time link for suppliers to upload documents directly into an encrypted repository. This method bypasses insecure email attachments and creates a clear, time-stamped audit trail of what was submitted, when, and by whom.

The objective is to make it easy for the supplier to provide evidence securely and difficult for any party to dispute its origin or integrity. This builds a defensible record.

Once evidence is received, it must be evaluated by comparing submitted documents against questionnaire responses and internal risk criteria. Verification is a human-led process of critical analysis, supported by a system that ensures the evidence is authentic and accessible.

Managing the Third-Party Assessment Lifecycle

Supply chain due diligence is not a one-time event; it is a continuous cycle of assessment, verification, and monitoring. This process is a significant test for Europe's IT industry. A recent study found that only 19% of firms have full visibility into their technology supply chains, despite sustainability being a board-level priority.

This represents a major vulnerability. Hardware from Asia, complex software dependencies, and cloud partnerships can conceal Scope 3 emissions or other risks that regulators under CSRD now require evidence on. With the ESG due diligence market expected to grow at a 13.0% CAGR globally, the pressure for rigorous verification will intensify. More insights on this market are available from Intel Market Research.

A mature program includes several key stages:

- Initial Onboarding Assessment: A comprehensive evaluation before a contract is signed.

- Periodic Re-assessment: Annual or biennial reviews to track changes and ensure ongoing compliance.

- Event-Driven Reviews: Triggered by specific events, such as a security incident at a vendor, a change in ownership, or new regulatory demands.

By treating third-party assessments as a continuous cycle, an organization embeds ESG directly into its procurement and vendor management functions. This demonstrates proactive governance, turning a compliance requirement into a strategic tool for building a more resilient supply chain.

Preparing Defensible, Audit-Ready Reports

The final stage of the ESG due diligence process is the construction of a coherent, defensible report. The objective is to present a clear narrative that demonstrates a mature, systematic governance process to an auditor or regulator.

A defensible report is characterized by complete traceability. It must show an unbroken line from a high-level policy to the specific control designed to enforce it, and finally to the immutable evidence proving the control's effectiveness. This reframes an audit from an inspection into a straightforward verification of a well-engineered system.

Constructing the Narrative

The report’s structure must be logical and intuitive, guiding the auditor through the methodology, decisions, and outcomes without ambiguity. An effective report includes several core components:

- Scope Definition: A clear statement of what was included in the due diligence process and, equally important, what was excluded and why. These boundaries must be justified based on materiality and regulatory drivers.

- Risk Assessment Methodology: A detailed explanation of the criteria used to identify and prioritize risks, including how risk levels were defined and what factors influenced those classifications.

- Control Mapping: A direct link between ESG policies and operational controls, often visualized in a matrix showing each policy, its corresponding controls, and their assigned owners.

- Evidence Index: An organized catalogue of all collected evidence, indexed and linked directly to the specific controls they support.

This structured approach demonstrates that the process was deliberate and systematic.

The Role of Tooling in Report Generation

Manual report creation is time-consuming and prone to error. Modern tooling can automate the generation of audit packs, ensuring consistency and integrity. A dedicated system can assemble all necessary components—scope documents, control mappings, encrypted evidence—into a single, organized package.

This is becoming critical as regulatory demands increase. The CSRD's 2025-2026 rollout is compelling 49,000 firms across Europe to overhaul their data infrastructures, with IT and financial services expected to bear 65% of this compliance load in key countries like Germany and France. The ESG reporting software market, valued at $1.1 billion in 2026, is projected to reach $3.1 billion by 2033, growing at a 16.8% CAGR. Europe's share of that market is 30%, driven almost entirely by these new mandates. More details on these ESG market trends are available.

An ideal audit pack is a self-contained proof of process. It should not just present the findings but also verify the integrity of the due diligence process itself.

Ensuring Verifiable Process Integrity

A key feature of a robust system is its ability to include immutable logs and full version histories within the exported report. This provides an auditor with independent verification of the process's integrity. They can see the complete lifecycle of every piece of evidence: when it was requested, who uploaded it, when it was reviewed, and confirmation that it has not been altered. This level of traceability provides a powerful layer of assurance that extends beyond the evidence itself, confirming the soundness of the data collection and review system.

Ultimately, preparing an audit-ready report is the tangible expression of an organization's ESG governance. It is the culmination of a disciplined process designed to demonstrate accountability, control, and verifiable proof.

Common Questions on ESG Due Diligence

As organizations implement their environmental, social, and governance objectives, several common questions arise. For technical and compliance leaders, the primary challenge is translating high-level ESG principles into the specific language of systems, controls, and regulated environments.

The following answers address frequently asked questions, clarifying how ESG processes overlap with other governance functions. Proper alignment is key to integrating ESG due diligence into existing risk frameworks without creating redundant work.

How Does ESG Due Diligence Differ From Traditional Financial Due Diligence?

Both are forms of risk assessment, but their focus and evidence differ fundamentally. Financial due diligence is retrospective and forward-looking, analyzing historical performance and economic forecasts to determine valuation or creditworthiness. Its evidence consists of balance sheets, income statements, and cash flow projections.

ESG due diligence, in contrast, evaluates non-financial factors to assess long-term sustainability and operational resilience. The evidence is operational, not financial. It includes data center energy consumption reports, supplier audit certificates, policy documents with version histories, and incident response plans. In a regulated IT context, ESG is less about valuation and more about demonstrating systemic compliance and responsible governance to regulators.

What Is the Role of Automation in ESG Due Diligence?

Automation and AI are system components, not autonomous actors. Their function is to make a human-led process more efficient and precise. For example, an automated system can scan supplier documents to flag risk keywords or send scheduled evidence requests to control owners, reducing manual follow-up.

However, a human professional remains accountable for the outcome. An AI component may identify a pattern suggesting a supply chain risk, but it is the compliance manager who investigates, applies judgment, and determines the appropriate action.

The system provides structured data and flags anomalies; the human provides oversight, context, and the final decision. This distinction is critical for maintaining clear accountability, especially during an audit.

This division of labor positions technology as a tool to support governance, not to replace it.

How Can We Integrate ESG Into Frameworks Like DORA or NIS2?

Integration is a necessity, not an option. Managing ESG separately from operational resilience frameworks like DORA or cybersecurity mandates like NIS2 creates silos and duplicates effort. The key is to map common requirements.

DORA’s strict third-party risk management rules, for example, align directly with the ‘Social’ and ‘Governance’ components of ESG focused on supply chain integrity. A practical approach is to map controls across frameworks:

- Shared Control Objective: A control designed to vet a cloud provider’s security under NIS2 can be extended. The same process can be used to collect and evaluate evidence of its energy sourcing policies and labor practices, satisfying ESG requirements.

- Unified Evidence: A central platform can link a single piece of evidence—such as a SOC 2 report or a supplier code of conduct—to multiple controls across ESG, DORA, and NIS2. This provides a comprehensive view of risk.

By mapping these intersections, ESG is treated not as an additional compliance burden but as an integral part of overall operational resilience. This approach is more efficient and provides a far more defensible view of the organization's risk posture.

At AuditReady, we provide an operational evidence toolkit for regulated environments. Our system helps you define scope, map ownership, and manage encrypted evidence for frameworks like DORA and NIS2. We focus on clarity and traceability, enabling you to export audit-ready packs that prove your governance process is effective. Learn more about how we support defensible due diligence.